The Invasion of Malabar (1766–1790)

In 1766, at the age of 15, Tipu Sultan had his first opportunity to put his military training into practice when he accompanied his father on an invasion of Malabar. Following the Siege of Tellicherry in Thalassery in North Malabar, Hyder Ali began to lose control over his territories in the region. Tipu Sultan intervened, arriving from Mysore to assert authority over Malabar.

The culmination of this campaign was the Battle of the Nedumkotta (1789–90). However, due to factors such as the monsoon flood, staunch resistance from Travancore forces, and news of the British attack on Srirangapatnam, Tipu Sultan was compelled to retreat.

Third Anglo-Mysore War

In 1789, Tipu Sultan contested the acquisition of two Dutch-held fortresses in Cochin by Dharma Raja of Travancore. He amassed troops at Coimbatore in December 1789 and launched an attack on the lines of Travancore on 28 December, aware of Travancore’s alliance with the British East India Company according to the Treaty of Mangalore. However, due to the strong resistance from the Travancore army, Tipu Sultan failed to break through their lines, prompting the Maharajah of Travancore to seek assistance from the East India Company.

In response, Lord Cornwallis mobilized company and British military forces, forming alliances with the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad to oppose Tipu Sultan. In 1790, company forces advanced, gaining control of much of the Coimbatore district. Despite Tipu Sultan’s counter-attack and the subsequent regaining of territory, the British maintained control over Coimbatore itself. Tipu Sultan then moved into the Carnatic, reaching Pondicherry in an unsuccessful attempt to involve the French in the conflict.

By 1791, Tipu Sultan faced advances on all fronts, with the main British force under Cornwallis capturing Bangalore and threatening Srirangapatna. Tipu Sultan employed a “scorched earth” policy to deprive the British of local resources and harassed their supply lines and communication. This tactic forced Cornwallis to withdraw to Bangalore instead of attempting a siege of Srirangapatna.

In 1792, Tipu Sultan’s campaign suffered a setback. The allied army, well-supplied, prevented Tipu Sultan from preventing the junction of forces from Bangalore and Bombay before Srirangapatna. After about two weeks of siege, Tipu Sultan initiated negotiations for surrender terms.

As a result of the ensuing treaty, he was compelled to cede half of his territories to the allies and deliver two of his sons as hostages until he paid the full war indemnity of three crores and thirty lakhs rupees to the British. Tipu Sultan paid the amount in two installments and retrieved his sons from Madras.

Also Read– Akbar’s assessment as national emperor-Mughal History

The Death of Tipu Sultan-Fourth Mysore War 1799

In 1798, Horatio Nelson’s victory over François-Paul Brueys D’Aigalliers at the Battle of the Nile in Egypt marked a significant turning point in European military history. However, it also had repercussions thousands of miles away in the Indian subcontinent. In 1799, three formidable armies descended upon Mysore—one from Bombay and two British, one of which boasted the participation of Arthur Wellesley. Their primary target was the capital city of Srirangapatna, as part of the Fourth Mysore War.

The disparity in numbers between the British forces and those of Tipu Sultan was staggering. While the British East India Company amassed over 60,000 soldiers, including approximately 4,000 Europeans and the rest Indian troops, Tipu Sultan could muster only around 30,000 soldiers. Despite this numerical disadvantage, Tipu Sultan’s resolve remained steadfast, bolstered by his belief in the righteousness of his cause.

However, internal betrayal dealt a devastating blow to Tipu Sultan’s defense efforts. His ministers collaborated with the British, weakening the city’s walls and paving the way for the invaders. This treachery proved to be a decisive factor in the fall of Srirangapatna.

As the British breached the city walls, French military advisers urged Tipu Sultan to escape via secret passages and continue the fight from other forts. Yet, Tipu Sultan, embodying the spirit of a warrior, steadfastly refused, declaring, “Better to live one day as a tiger than a thousand years as a sheep.” His decision to remain and face his fate head-on epitomized his unwavering courage and determination.

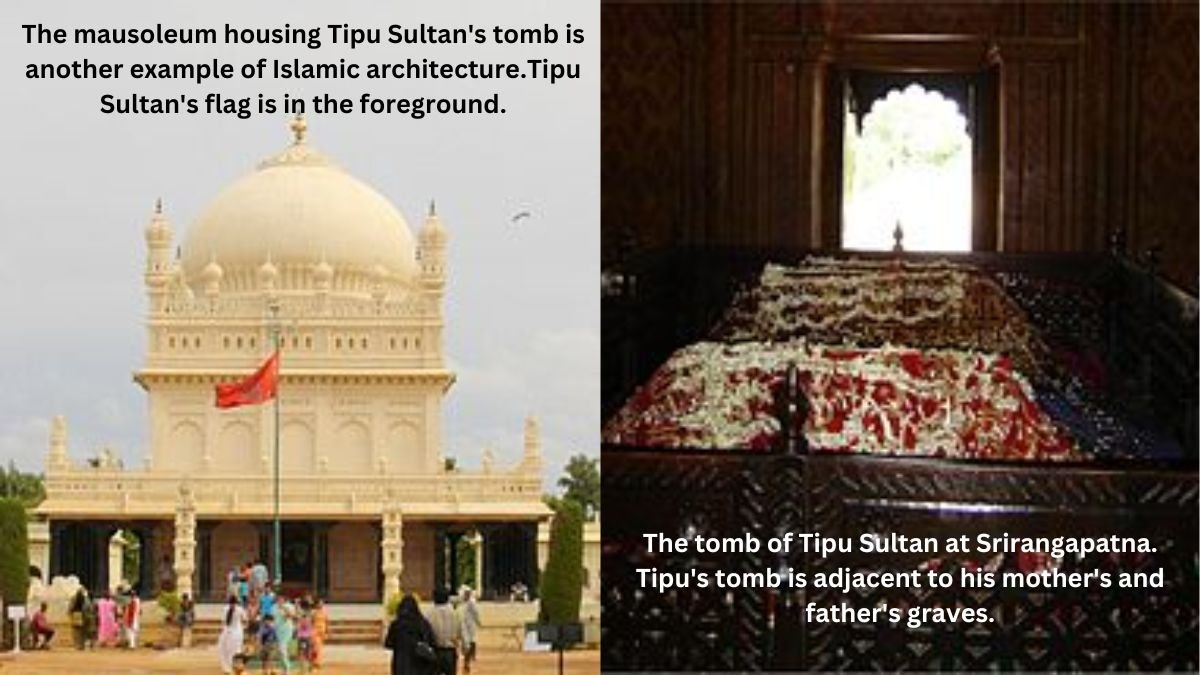

The fateful moment came at the Hoally (Diddy) Gateway, situated 300 yards from the northeastern angle of the Srirangapatna Fort. It was here that Tipu Sultan met his end, bravely defending his capital until his last breath. His body was laid to rest the following afternoon at the Gumaz, next to the grave of his father, Hyder Ali.

Also Read– Nature and Significance of British Colonialism-Advantages and Disadvantages

In the aftermath of Tipu Sultan’s demise, jubilant celebrations erupted in Britain. Authors, playwrights, and painters commemorated the event through various works of art, highlighting the significance of his defeat to the British Empire. The death of Tipu Sultan was even commemorated with a public holiday in Britain, underscoring the magnitude of its impact on the colonial power’s imperial ambitions in India.

Relation With the Ottoman Empire

In 1787, Tipu Sultan dispatched an embassy to the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, appealing to Sultan Abdul Hamid I for urgent assistance against the British East India Company. Tipu Sultan requested military support and expertise from the Ottoman Empire, along with permission to contribute to the maintenance of Islamic shrines in Mecca, Medina, Najaf, and Karbala. However, the Ottoman Empire was grappling with internal crises and conflicts, including the Austro-Ottoman War and tensions with the Russian Empire.

With an imperative need for a British alliance to counter Russian threats, the Ottomans were unable to extend significant aid to Tipu Sultan. Consequently, Tipu Sultan’s ambassadors returned home empty-handed, receiving only symbolic gifts from the Ottoman leadership. Despite these challenges, Tipu Sultan’s correspondence with the Ottoman Empire, particularly with Sultan Selim III, persisted until his final battle in 1799.

Relation With Persia and Oman

Continuing the diplomatic traditions of his father, Tipu Sultan maintained friendly relations with Mohammad Ali Khan of the Zand Dynasty in Persia and Hamad bin Said, the ruler of the Sultanate of Oman.

Relation With Qing China

Tipu Sultan’s engagement with silk production began in the early 1780s when he received an ambassador from the Qing dynasty of China. Enthralled by the gift of silk cloth, Tipu Sultan resolved to introduce silk production in Mysore. He dispatched an envoy to China, who returned after twelve years, marking the inception of silk cultivation in the region.

Relation With France

Aligning with his father’s policies, Tipu Sultan sought alliances with France, the primary European power capable of challenging the British East India Company in the subcontinent. French initiatives included treaties with Peshwa Madhu Rao Narayan and ceremonial gestures such as presenting a portrait of Louis XVI to Hyder Ali. Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt was viewed as a potential opportunity for alliance, although British interception of diplomatic correspondence thwarted direct communication between Tipu Sultan and Napoleon.

Social System

Judicial System

Tipu Sultan implemented a judicial system that appointed judges from both Hindu and Muslim communities to oversee legal matters. Each province had a Qadi for Muslims and a Pandit for Hindus, ensuring representation and fairness in the legal system.

Moral Administration

Under Tipu Sultan’s rule, the consumption of liquor, prostitution, and the cultivation of psychedelics like Cannabis were strictly prohibited. Additionally, Tipu Sultan enacted measures to discourage practices like polyandry, emphasizing moral conduct and social order.

Religious Policy

While personally devout, Tipu Sultan demonstrated religious tolerance through his patronage of mosques and temples. He made regular endowments to Hindu temples and appointed Hindu officers in his administration. However, his religious policies remain controversial, with accounts of religious persecution and forced conversions by Tipu Sultan cited by some historians. These narratives, largely propagated by early British authors, are viewed with skepticism by modern scholars who question their reliability and potential bias.

British Accounts

Historians such as Brittlebank, Hasan, Chetty, Habib, and Saletare contend that much of the contentious narratives surrounding Tipu Sultan’s alleged religious persecution of Hindus and Christians stem from the writings of early British authors who held biases against Tipu Sultan and sought to discredit his rule. Figures like James Kirkpatrick and Mark Wilks, whose accounts are frequently cited, are deemed unreliable and potentially fabricated by these scholars. A. S. Chetty specifically criticizes Wilks’ narrative, casting doubt on its veracity.

Irfan Habib and Mohibbul Hasan assert that these early British authors had vested interests in portraying Tipu Sultan as a tyrant who needed to be overthrown by the British to liberate Mysore. They argue that the British sought to justify their intervention and annexation of Mysore by vilifying Tipu Sultan.

Brittlebank also warns against uncritical acceptance of Wilks and Kirkpatrick’s accounts, emphasizing their active involvement in conflicts against Tipu Sultan and their close ties to the British administrations of Lord Cornwallis and Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley. Therefore, scholars advocate for scrutiny and contextualization of these accounts when assessing Tipu Sultan’s reign and policies.

List of Tipu Sultan’s Sons

| Son’s Name | Year |

|---|---|

| Shahzada Sayyid Shareef Hyder Ali Khan Sultan | 1771 – 30 July 1815 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Abdul Khaliq Khan Sultan | 1782 – 12 September 1806 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Muhi-ud-din Ali Khan Sultan | 1782 – 30 September 1811 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Mu’izz-ud-din Ali Khan Sultan | 1783 – 30 March 1818 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Mi’raj-ud-din Ali Khan Sultan | 1784? –? |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Mu’in-ud-din Ali Khan Sultan | 1784? –? |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Muhammad Yasin Khan Sultan | 1784 – 15 March 1849 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Muhammad Subhan Khan Sultan | 1785 – 27 September 1845 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Muhammad Shukrullah Khan Sultan | 1785 – 25 September 1830 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Sarwar-ud-din Khan Sultan | 1790 – 20 October 1833 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Muhammad Nizam-ud-din Khan Sultan | 1791 – 20 October 1791 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Muhammad Jamal-ud-din Khan Sultan | 1795 – 13 November 1842 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Munir-ud-din Khan Sultan | 1795 – 1 December 1837 |

| Shahzada Sir Sayyid walShareef Ghulam Muhammad Sultan Sahib, KCSI | March 1795 – 11 August 1872 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Ghulam Ahmad Khan Sultan | 1796 – 11 April 1824 |

| Shahzada Sayyid walShareef Hashmath Ali Khan Sultan | died at birth |

FAQs about Tipu Sultan

Question 1- Who was Tipu Sultan?

Answer: – Tipu Sultan, also known as Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, was a ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. He was born on November 20, 1751, and died on May 4, 1799. Tipu Sultan was known for his resistance against British expansionism in India during the late 18th century.

Question 2- How many wives did Tipu Sultan have?

Answer: – Tipu Sultan had several wives. The exact number is not precisely documented, but historical records indicate that he had multiple wives during his lifetime.

Question 3- Was Tipu Sultan a Mughal?

Answer: No, Tipu Sultan was not a Mughal. He was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore, which was located in present-day Karnataka, India. However, Tipu Sultan maintained diplomatic relations with the Mughal Empire and acknowledged nominal allegiance to the Mughal emperor.

Question 4- What language did Tipu Sultan speak?

Answer: Tipu Sultan was fluent in multiple languages. He primarily spoke Kannada, the native language of the region where Mysore was located. Additionally, he was proficient in Urdu, Persian, and Arabic, which were commonly used in administrative and diplomatic affairs during his time.