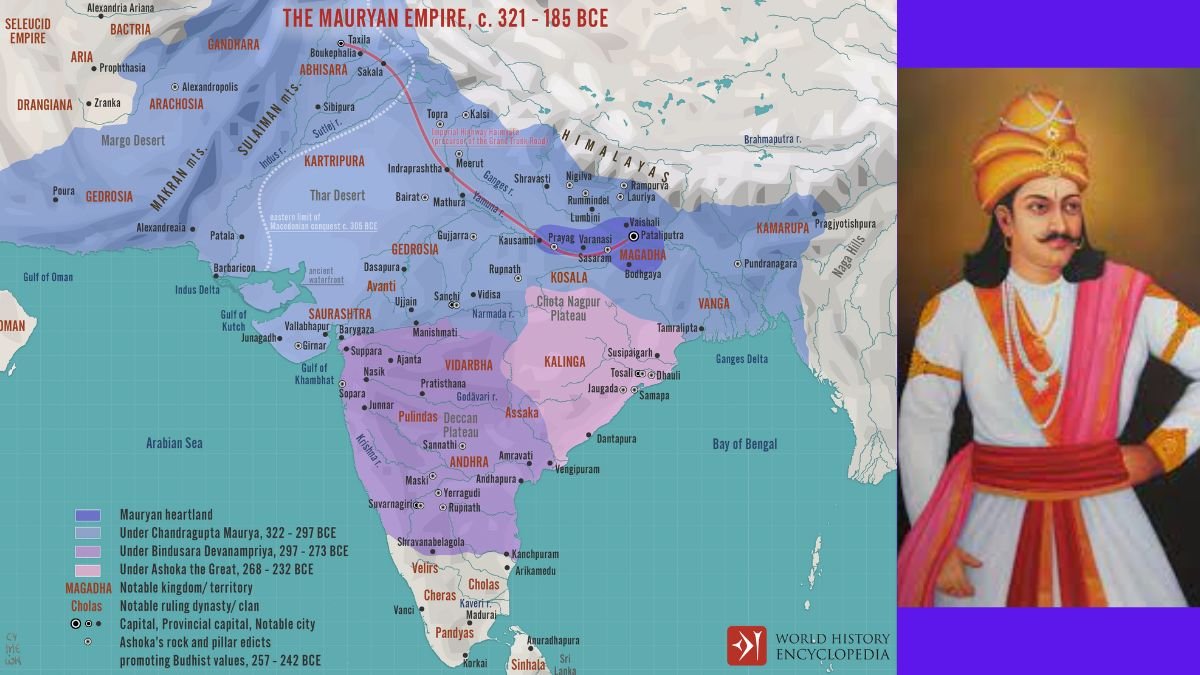

Introduction: In the annals of ancient Indian history, the Maurya Empire stands out as a remarkable testament to the visionary leadership of Chandragupta Maurya and the strategic acumen of Chanakya. This empire, which spanned from 321 BCE to 185 BCE, holds the distinction of being the first pan-Indian monarchy, exerting control over the vast expanse of the Indian subcontinent.

The Rise under Chandragupta Maurya:

As the influence of Alexander the Great waned, Chandragupta Maurya seized the opportunity to initiate land consolidation in the Magadha region. In the aftermath of Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, Chandragupta orchestrated the overthrow of the formidable Nanda kingdom in eastern India, laying the foundation for the Mauryan Empire. The Nanda Empire, known for its substantial power and prosperity, succumbed to the emergence of the Mauryas as a dominant force in the region.

Expansion and Dominance:

Under the reign of Emperor Ashoka, the Maurya Empire reached its zenith, extending its dominion over an expansive territory exceeding five million square kilometers. Geographically, the empire was encircled by natural barriers, with the Himalayas, the Ganges River to the north, the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Indus River to the west, and the Arabian Sea to the west. This strategic positioning solidified its status as the largest empire on the Indian subcontinent during its peak.

Chanakya’s Enduring Influence:

A pivotal figure in the rise and consolidation of the Maurya Empire, Chanakya, also known as Kautilya, served as Chandragupta’s Prime Minister. His strategic brilliance and statesmanship played a crucial role in shaping the course of the empire’s history. The contributions of Chanakya stand as a testament to the intellectual and political prowess that underpinned the Maurya Empire’s success.

Who Was The Foundation of the Mauryan Empire:

In the fourth century BC, Chandragupta Maurya laid the sturdy foundation for what would become the illustrious Mauryan Empire. His remarkable journey involved the meticulous construction of a formidable army and the establishment of a significant empire, marking the initiation of a transformative era.

Overthrowing Dynasties and Uniting the Subcontinent:

Chandragupta’s strategic prowess manifested in the overthrow of the Greek Satraps in the North-West Frontier and the Nandas of Magadha. This series of victories culminated in the unification of the majority of the Indian subcontinent under the banner of his one-party rule. His ascendancy marked a pivotal moment in Indian history.

Also Read– History and Achievements of Skandagupta

The First Mauryan Emperor – Smarat Chakravartin:

Chandragupta Maurya ascended to the throne as the inaugural Mauryan emperor, earning the epithet of Smarat Chakravartin, or the Universal Emperor. Collaborating closely with Chanakya, he orchestrated the downfall of Dhananand, the last emperor of the Nanda Dynasty, paving the way for a new era under Mauryan rule.

Diplomacy and Marriage with Selucus Nicator:

In a diplomatic triumph, Chandragupta Maurya engaged with Selucus Nicator, a general under Alexander, in the year 321 BC. Negotiating an agreement, he sealed the deal by marrying Selucus Nicator’s daughter. As part of the pact, Chandragupta received 500 elephants and control over a portion of North Western India, showcasing the astuteness of his diplomatic endeavors.

The Greek Perspective and Jain Conversion:

Greek diplomat Megasthenese documented his visit during Chandragupta Maurya’s reign, referring to him as Sandrokottos. This historical interaction provides a unique glimpse into the Mauryan Empire from an external perspective. Later in life, influenced by Bhadrabahu, Chandragupta converted to Jainism and embarked on a spiritual journey to Shravanabelagola. It was there, amidst the Chandragiri Hills near Mangalore, Karnataka, that he chose to embrace a slow path of self-imposed starvation, a poignant conclusion to his remarkable life.

Also Read– Cultural Ties Between India and the Greco-Roman World

| Ruler | Span of Rule |

|---|---|

| Chandragupta Maurya | 321-297 BC |

| Bindusara | 297-272 BC |

| Ashoka | 272-232 BC |

| Dasaratha | 252–224 BC |

| Samprati | 224-215 BC |

| Salisuka | 215-202 BC |

| Devavarman | 202-195 BC |

| Satadhanvan | 195-187 BC |

| Brihadratha | 187-185 BC |

Chandragupta Maurya’s Leadership (324/321 – 297 BCE):

Chandragupta Maurya, alongside the strategic genius Chanakya/Kautilya, played a pivotal role in laying the foundation of the illustrious Mauryan dynasty. Their collaboration marked the beginning of an era that shaped the destiny of ancient India.

Military Triumphs and Diplomacy:

According to the accounts of the Greek author Justin, Chandragupta Maurya’s military prowess was legendary, claiming that he conquered the entirety of India with an army numbering 600,000. His strategic acumen led to the liberation of northwestern India from the rule of Seleucus, the Greek ruler of the region west of the Indus. The ensuing battle between Chandragupta and the Greek viceroy ended in a negotiated peace, with Seleucus ceding eastern Afghanistan, Baluchistan, and the region west of the Indus River, a strategic exchange for 500 elephants.

Architect of the Mauryan Empire:

Chandragupta Maurya’s visionary leadership was instrumental in the construction of the vast Mauryan Empire. Initially establishing his influence in Punjab, he expanded eastward, capturing the Magadhan region. The empire stretched across the Deccan, significant portions of western and northern India, Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar. Except for Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and some northeastern regions, the Mauryans held dominion over the entire Indian subcontinent.

Legacy and Geographic Extent:

Chandragupta Maurya’s legacy lies in the enduring impact of the Mauryan Empire. His strategic maneuvering and statecraft allowed the Mauryans to govern a vast expanse, showcasing their influence over the Deccan and substantial territories in western and northern India. The empire’s reach extended to Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar, solidifying its dominance over the majority of the Indian subcontinent during this remarkable period in ancient history.

Bindusara’s Reign (297 – 273 BCE):

Bindusara, the successor to Chandragupta Maurya, wielded power and influence during his reign, leaving an indelible mark on the Mauryan Empire’s history.

Epithets and Prophecies:

Known by Greek scholars as Amitrochates (destroyer of foes) and by the Mahabhasya as Amitraghata (killer of enemies), Bindusara’s rule was characterized by his formidable presence and military prowess. The Ajivika sect even narrates a fascinating prophecy foretelling the future glory of Bindusara’s son, Ashoka.

Conquests and Territorial Expansion:

Bindusara’s military campaigns were expansive, stretching from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal. His conquests solidified the Mauryan Empire’s control over a vast region, showcasing his ability to extend dominion across diverse landscapes.

Chanakya’s Influence and Diplomacy:

According to Tibetan monk Taranatha, one of Bindusara’s notable lords, Chanakya, orchestrated the overthrow of nobles and kings in 16 towns, establishing himself as the ruler of the region between the eastern and western seas. Bindusara’s diplomatic acumen was evident through his contacts with Western kingdoms, as noted by Greek sources. Strabo highlights that Deimachus was sent as an ambassador to Bindusara’s court by Antiochus, the Syrian monarch.

Religious Affiliation and Empire’s Reach:

Bindusara’s intriguing connection with the Ajivika sect adds a layer of complexity to his reign. It is believed that he became a member of this sect during his rule. Geographically, the Mauryan Empire, under Bindusara’s governance, expanded its sway nearly across the entire subcontinent, reaching as far south as Karnataka.

Ashoka The Great: A Legacy of Transformation and Enlightenment

Ashoka’s Ascension (268 – 232 BCE):

Following the demise of Bindusara in 273 BCE, the Mauryan Empire faced a succession dispute that lasted for four years. Despite Susima, Bindusara’s designated successor, Ashoka ascended to the throne through the support of Minister Radhagupta and a tumultuous event involving the murder of 99 brothers.

Early Role and Leadership:

Ashoka’s journey to greatness began as the viceroy of Taxila and Ujjain during Bindusara’s reign. These strategic cities were hubs for trade operations, shaping Ashoka’s understanding of governance and administration.

Innovations in Communication:

Ashoka’s reign marked a significant departure in governance. Recognized as one of history’s greatest kings, he pioneered the use of inscriptions as a means of communication with his subjects. This innovative approach allowed him to maintain a connection with the people under his rule.

Titles and Personal Identity:

The emperor bore several names that reflected his multifaceted persona. Known as Buddhashakya (Maski edict), Dharmasoka (Sarnath inscription), Devanampiya (beloved of the gods), and Piyadassi (of pleasing appearance), these titles were chronicled in Buddhist texts such as Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa from Sri Lanka.

Mauryan Art and Architecture

Chandragupta Maurya’s Legacy at Kumhrar:

The architectural splendor of the Mauryan Empire, notably during Chandragupta Maurya’s reign, is exemplified by the grandeur of the former palace at Pataliputra, now known as Kumhrar in Patna. This colossal structure, the largest from the era, unveils the empire’s architectural prowess and historical significance.

Historical Insights from Megasthenes, Fa-Hien, and Hiuen Tsang:

Megasthenes‘ work “Indica” provides valuable insights into the Mauryan Dynasty, complemented by similar descriptions from travelers like Fa-Hien and the monk Hiuen Tsang. These historical accounts contribute to our understanding of the architecture and cultural richness of the empire.

Discoveries at Kumhrar:

Excavations at Kumhrar have revealed remnants of diverse structures, suggesting a complex of buildings. A prominent feature was a sizable pillared hall constructed on a high wood substratum. These findings offer a glimpse into the architectural diversity and grandeur of the Mauryan era.

Mauryan Stonework During Ashoka’s Reign:

The Ashokan era witnessed remarkable achievements in stonework, featuring lion sculptures, stupa railings, free-standing pillars, and monumental structures. The precision and artistry reached such heights that even small stone artifacts were polished to a glossy sheen reminiscent of exquisite enamel.

Sanchi Stupa, a testament to Ashoka’s architectural vision, stands as an enduring masterpiece. Constructed on the foundation laid by Ashoka, the stupa’s interior structure utilized unburned brick, while its outer walls boasted the elegance of roasted brick. Sanchi Stupa remains an iconic example of Mauryan architectural excellence.

Ashokan Stupas and Monuments:

Ashoka’s architectural contributions extended to the construction of stupas adorned with Buddha images. Notable examples include the renowned Sanchi Stupa, as well as structures at Nandangarh, Nagarjunakonda, Bharhut, Amaravati, Bodhgaya, and others. These monuments showcase the empire’s commitment to creating enduring symbols of religious and cultural significance.

Mauryan Empire Governance

Centralized Authority under the Emperor:

The Mauryan Empire’s governance was marked by a highly centralized system, with the Emperor serving as the supreme authority and the ultimate source of power. This centralized structure laid the foundation for effective rule and administration.

Council of Ministers – Mantriparishad:

Assisting the Emperor in decision-making was the Council of Ministers, referred to as “Mantriparishad,” with its members known as “Mantris.” At the helm of this council was the “Mantriparishad-Adhyakshya,” serving as a modern-day prime minister, overseeing the deliberations and actions of the council.

Tiers of Administration:

The administration featured distinct tiers, with “Tirthas” occupying the highest level, totaling 18 officials. Above them were the “Adhyakshyas,” numbering twenty, responsible for both military and economic matters. The hierarchical structure included senior government employees called “Mahamattas” and high-ranking representatives known as “Amatyas,” performing crucial judicial and administrative roles.

Departmentalization and Secretariat:

To streamline governance, a secretariat comprising various departments was established under the Adhyakshyas. The Arthashastra detailed specific Adhyakshyas for diverse areas such as trade, warehouses, gold, ships, agriculture, cows, horses, cities, chariots, the mint, and troops.

Specialized Superintendents:

The administration appointed officers for specific functions, including “Rajjukas” for land measurement and boundary marking, “Sansthadhyasksha” as mint superintendents, “Samasthadhyasksha” as market superintendents, and others like “Sulkaadhyaksha,” “Sitaadhyaksha,” “Navadhyaksha,” “Lohadhyaksha,” “Pauthavadhyakhsa,” and “Akaradhyaksha” for tolls, agriculture, ships, ironworks, weights and measures, and mines, respectively.

Judiciary and Public Relations:

The administration had a well-defined judicial system, including “Vyavharika Mahamatta” as members of the judiciary. Public relations specialists in “Pulisanj” played a role in managing communication and interactions with the public.

Control over Key Aspects:

The Mauryan administration exercised control over crucial aspects of society, including the registration of births, deaths, immigrants, industries, trade, manufacturing, sales of commodities, and the collection of sales taxes. This comprehensive oversight ensured efficient governance and economic stability.

Local Administration in the Mauryan Empire:

| Administrative Level | Administrative Roles and Titles |

|---|---|

| Village | – Smallest Administrative Entity – Village Leader: Gramika – Villages Enjoyed High Autonomy |

| District/Province | – District Magistrates or Provincial Governors: Pradeshika |

| – Tax Collectors working for Pradeshikas: Sthanika | |

| Forts | – Fort Governors: Durgapala |

| Frontiers | – Frontier Governors: Antapala |

| Central Administration | – Accountant General: Akshapatala |

| – Scribes: Lipikaras |