This year, India is celebrating its 76th Independence Day, and many people also want to know how India got independence. The history of freedom and slavery runs almost simultaneously. Although, in this article, we will only briefly discuss the history of independence. Let us explore how India gained independence: A historical overview. Special article on Independence Day. Must read the article till the end.

History of Independence:

For many years, efforts have been made to analyze the developments of Indian nationalism in its social and historical context. Changes kept occurring on the stage of the Indian National Movement, and literature related to it continued to accumulate. Presenting different emerging scenes, historians kept raising various questions, such as how India’s national independence came about. Did this freedom come due to only one person, class, or party, or did different individuals and classes contribute to it?

The literature available in the context of these questions, and in which attempts have been made to find answers, lacks a scientific approach. To understand the trends of Indian national independence, it is crucial to comprehend those economic, political, social, educational, cultural, and ideological currents and movements.

The process of the development of nationalism in India has been very complex. Before the arrival of the British, India’s social structure was unique in many ways, and its economy differed from the pre-capitalist societies of European countries.

Britain made radical changes in the economic structure of Indian society to serve its interests, established a centralized state system, and created a modern education system, a new communication system, and other new institutions. As a result, new social classes emerged, a new consciousness erupted among the Indian public, and the base of the national struggle became wider and wider.

As the Indian National Liberation Movement progressed from one phase to another, along with the broadening of its social base, social and political consciousness increased in the new classes born as a result of the new economy. Where social, economic, and structural changes took place in many countries, Indian people’s lives also changed at a rapid pace. During this time, the Indian people went through a period of social, political, and economic changes. The pace of events during the Second World War was very rapid. At this time, the Indian people’s struggle for national independence became very intense.

World War II and Arbitrary Attitude by the British Government:

When the new British government declared war on Germany in 1939, it tried to adopt exactly the same attitude that was taken during the First World War. Shortly after the declaration of war, the Viceroy, without consulting the representatives of the Indian people, declared India at war. The ‘Government of India (Amendment) Act’ was also passed in the British Parliament, under which the Viceroy was given the power to suspend the functioning of the constitution.

The Defense of India Ordinance of 1939 granted the central government the power to rule by the promulgation of ordinances. The Central Government could, by edict, promulgate such laws as it considered necessary for the defense of British India, the security of life, public order, the efficient conduct of war, or the maintenance of the supply of resources and services necessary for society. It could ban other means of communication, arrest anyone without a warrant, and punish law-breakers with fines, the death penalty, or life imprisonment.

In this way, exceptionally harsh laws were enacted to maintain the despotic regime, and the Indian people had to join the war unwillingly. Thus, due to the Viceroy assuming autocratic powers and arbitrarily involving India in the war, deep resentment arose among the Indian public, and they adopted a policy of protest.

Indian National Congress and the British Government:

The turn of events quickly made it clear that the situation was not the same as in 1914. The Indian National Congress denounced the war as imperialist and refused to associate with it. In one of its statements, its Working Committee declared, “The Council cannot associate itself with or give any cooperation to a war which is being waged by the imperialist forces and whose object is to strengthen imperialism everywhere, including in India.”

The Executive Council, therefore, invited the British Government to declare in clear terms how their war objectives would apply to India in the context of democracy and imperialism and the new order, and how they would be put into practice at present. Do they include in this the recognition of India as an independent nation whose policy will be governed by the will of its people?” (September 1939).

In response, the British government reiterated its promise that India would be given Dominion status in the future. The Viceroy’s negative reply led to the resignation of all the Congress ministries in October 1939.

As the threat of war deepened in the summer of 1940, the Congress expressed its willingness to cooperate with the British government in the war, provided that Britain accepted the demand for national independence for India and established a ‘provisional national government at the center’. This government may be temporary, but it should have the confidence of all the elected members of the Central Legislature.

However, the British government rejected this proposal of the Congress and stated that the representatives of the Muslim community, the Muslim League, and the princely states would not agree to it.

Personal Civil Disobedience:

After repeatedly failing to achieve national independence through negotiations, Congress finally launched the Individual Civil Disobedience Movement in October 1940. At a time when Congress itself described the war as being fought ‘in furtherance of imperialist objectives’, and India had an opportunity to intensify its freedom struggle, the mass civil disobedience movement was refused by Congress. This signaled that the Congress leadership did not want to seriously hinder Britain in the war.

Reginald Coupland acknowledged that “the movement did not cause much difficulty to the government.”

Change in International Situation:

Since the beginning of the Second World War, there have been drastic changes in the international scene from the economic and political point of view. The Indian people also did not remain untouched by these changes. The contradictions and class antagonisms became very intense in the world, as a result of which the world of human society became a theater of intense conflicts. To understand the fact of how freedom came to India, it is essential to understand the world’s development and economic structure during the war and in the post-war period.

When the democratic imperialist countries – Britain, the United States of America, and France – defended themselves against fascist invasion, they controlled and owned a large part of the world’s economic sphere.

During this time when Britain, France, and Holland had their empires, the USA was not a colonial power, but its economic status was increasing day by day, and it wanted to establish permanent dominance over the world.

Thus, while it was a war to forcibly retain its economic territories, it was also aimed at violently taking away the colonies.

Rise of Great American Imperialism:

After the war, the economic, political, and military power of other imperialist powers, except the United States of America, became very weak. There were crises in their empires, and their financial and economic status was severely degraded.

After World War II, US imperialism emerged most powerfully in the economic, political, and military fields. After the end of the war, there was a rapid increase in the production power and capital accumulation of American capitalism. Therefore, it also needed the largest economic sector.

The US invaded not only the old Asian countries but also colonies, semi-colonies, and the commercial and financial spheres of underdeveloped new countries and tried to drive out other imperialists. Gradually, it adopted the role of the protector of the world capitalist system while expanding the only prosperous and powerful capitalism.

Military and Economic Decline of Britain and France:

After the war, the economic and military positions of Britain and France declined greatly. With their economies in ruins, they had to look to America for their revival. When these imperialist countries were economically subjugated, their political positions also faltered. India also gained freedom from the clutches of imperialist rule to some extent. Although political power was transferred, this transfer was in the hands of the bourgeoisie, so that the foreign capital invested here could be safeguarded.

Russia as a Driving Force:

As a result of the Second World War, the influence of imperialism began to decline. The colonial system of capitalism that enslaved nations and forced their people to endure inhuman torture saw its colonial system starting to crumble.

In this situation, the Russian system became a great example in front of the freedom movements of the colonies and dependent countries. Progressive Indians welcomed the establishment of the Russian socialist system and considered it an inspiration, heralding an end to human exploitation and oppression. The Russian system became an important factor in India from an ideological, political, and organizational point of view. Mass organized action began in the country. Progress was made in the formation of the toiling Indian working class, and trade unions were organized in Bombay and Calcutta. Previously, trade unions were functioning only in a charitable manner.

Goals such as the ‘establishment of socialism’ and the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ were revealed for the first time in the Indian National Constitution. Emphasis was placed on organizing both industrial and agricultural workers. Regular relations between Indian patriots and the international communist and labor movement started to be established. For the first time, communists started organizing the toiling masses on a class basis, spread self-consciousness among them, and started training toward the goal of socialism.

Economic Development during the War: Unattractive Opportunities for the Indian Bourgeoisie and the Changing Position of the Indian Capitalists

Through its economic and political policies, Britain hindered the independence and industrialization of India. In particular, it did not allow heavy industries to develop and thus prevented the creation of an independent national economy.

During World War II, when the economies of Britain and other developed industrial countries were focused on meeting the war requirements, Indian industrialists got a golden opportunity to capture the Indian markets and expand their industries. Due to inflationary market conditions, the pace of production in established industries increased rapidly. Despite this, the British government did not want India to develop into a strong industrial power, as it could later prove to be a major rival to Britain itself. Hence, capital import was not allowed.

For this reason, Indian industrialists were not able to establish new industrial enterprises. Additionally, due to the halt in the import of goods, they had to work excessively with existing resources. As a result, Indian industries could not progress administratively during the war.

However, due to the increasing inflation during the war, the general public had to suffer a lot. They struggled to meet even their basic needs, and the rising cost of living pushed many into poverty. Despite this, industrialists, vendors, and traders made substantial profits. At the same time, capitalists claimed to be patriotic and asserted that they had always represented national interests. Their motivation stemmed from grievances against the British rulers.

The main complaint of the Indian merchant and capitalist class was that the Europeans received more favorable treatment from the government compared to them, while Indians faced severe restrictions. Gradually, awareness arose within the industrial class, and they began participating in the national movement in the first decade of the twentieth century. This class was drawn to the Indian National Congress and started supporting the boycott of foreign goods and the Swadeshi movement, as it served their class interests.

The Indian industry received a significant boost from the Swadeshi movement. Capitalists were receptive to the concept of class coordination theory advocated in Gandhian ideology, as their existence was threatened by the theory of class struggle. Capitalists like Birla, Sarabhai, and Bajaj supported the Congress and funded its programs.

Like other classes, the capitalist class formed organizations such as the Bombay Mill Owners Association, Indian Jute Mill Association, and Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry Federation to protect their interests.

The capital raised during the war was later used to acquire British enterprises, and a trend of amalgamation of British and Indian capital emerged. British capitalism, weakened by the war, adopted this new strategy to maintain its influence. This involved running English and Indian industries jointly in India. While there was no integration in joint industries before the war, a new era of integration of Indian and British capital began.

Hence, Indian capitalists and merchants participated in the national movement to safeguard their class interests not only during British rule but also in the future. The New Situation in the War and the Cripps Mission

Following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in late 1941, the war alliance between Britain, France, and other countries extended to the United Nations, which included the Soviet Union, the United States, and China. The Atlantic Charter, proposed by Britain and the United States, declared the war’s objective to be the restoration of sovereignty and government to those who had been forcibly deprived of these rights, giving hope to the Congress leaders.

The Japanese army was advancing towards Asia as a conqueror, prompting Britain to consider it necessary to satisfy India. Without the support of the Indian public, countering any Japanese attack on India was impossible. Consequently, the British ‘War Cabinet’ dispatched the ‘Cripps Mission’ to India to negotiate a political settlement with Indian leaders. However, this attempt failed as Britain rejected the demand of Indian nationalist leaders to establish a government with full powers, leading to the breakdown of the conversation. Another shortcoming was the failure of the Indian National Congress and the Muslim population to unite and present their national demand to the British Government.

End of the war and growing economic and political discontent

By arresting prominent Congress leaders in 1942 and declaring the Congress as an illegal organization, the government quashed any movement. As a result, riots erupted across the country, which were suppressed due to a lack of leadership and a coherent struggle plan. The government crushed the organized struggle by the revolutionary underground parties.

During the Second World War, the national consciousness among the Indian people deepened, and the demand for national independence was put before the government in a more aggressive manner. There was serious political and economic discontent in India after the war ended. The impoverishment of the public filled their minds with a feeling of rebellion. The public had a strong desire for economic and political liberation, and this dissatisfaction turned the country into a theater of mass struggles.

The food situation worsened in late 1945. Crops failed severely in Madras, Bombay, Hyderabad, and central India. Exploitation by landlords and usurers became intolerable for farmers, workers were laid off due to low production in factories, wages were reduced, and attempts were made to abolish bonuses. Additionally, trends of black marketing and profiteering began to emerge, causing significant increases in the prices of daily necessities.

As a result, discontent grew among workers, farmers, and low- to middle-income people, intensifying the class struggle. The Indian public’s protest against British rule escalated rapidly. Due to various intense movements in different parts of the country, it became challenging for the British to maintain control in India. The Congress enjoyed widespread public support across the country.

During the Second World War, people worldwide witnessed the power of socialist economies. The proletarian socialist revolution in independent capitalist countries, along with the people in dependent countries, rapidly moved toward national emancipation.

Following Japan’s surrender, people in Indo-Asia, Indo-China, Burma, Malaya, and the Philippines embarked on armed struggles for their independence. The wave of revolution was also seen in India after the war’s end. Some of the reasons for this wave were attempts to suppress the national liberation movements in Indo-China and Indo-Asia.

The sending of the Indian Army and the prosecution of Azad Hind Fauj officers were opposed by the Congress, the Communist Party, and the Muslim League. South-East Asia Day was celebrated on October 25, 1945. On that day, public meetings were held in major Indian cities, processions were organized, and slogans were raised: ‘Imperialists, move away from Southeast Asia.’ Dock workers in Bombay and Calcutta refused to load ships destined for Indo-Asia with munitions and food for the army.

In 1945 itself, Azad Hind Fauj officers were released and were soon given lengthy sentences. Therefore, all Indians unanimously opposed this action of the British rulers, and workers and office employees held processions in Calcutta. Buses and trams remained closed for several days. The general public set military vehicles on fire. Subhash’s brother, Saratchandra Bose, appealed on behalf of the Congress for students and workers to cease anti-government activities, while also stating that the Congress would achieve independence for the country through lawful and non-violent means.

Due to this Congress appeal, the general public withdrew from the movement. Several deaths occurred due to police and army firings over several days. Clashes between the general public and the police also erupted in Bombay, Delhi, and Madurai.

Mutiny by Navy and Army Unrest:

The most significant events of 1946 were the naval mutiny and army unrest. Their demands included the removal of discrimination between British and Indian personnel in the air force, granting Indian airmen equal rights as British airmen, and ensuring job opportunities after retirement from the army. Additionally, British officers’ mistreatment of Indian airmen led over 1500 Air Force personnel to present these demands to the government.

Shortly thereafter, the navy mutinied. The Royal Indian Navy (Royal Indian Navy) had been formed just before the Second World War, with most senior officers being British. Indian sailors did not receive the same privileges as the British, endured poor food quality, faced humiliation from British officers, received minimal shortage allowance, and were even required to return their uniforms. Despite repeated complaints to the British, these issues were ignored, with the response being, ‘Beggars cannot be choosers.’

Officers further suggested that those who couldn’t eat rice mixed with pebbles should clean the rice with their hands. As a result, sailors rebelled, and slogans like ‘British, Quit India’ appeared on barracks’ walls, for which Dutt was held responsible and arrested. Sailors responded by going on strike on February 18, 1946.

By February 19, the number of strikers reached 20,000. Congress and Muslim League flags were hoisted simultaneously on the ships, and sailors in naval uniforms conducted processions. The mutineers established a central strike committee and maintained strict discipline. The epicenter of this rebellion was Bombay, where people wholeheartedly supported them and sent food on ships. The Communist Party and Red Unions supported the seamen’s call in Bombay. On February 22, over 200,000 workers went on strike, holding processions and meetings at Kamgar Maidan, where Shripad Amrit Dange spoke.

In 1946-47, the form of labor movements underwent significant changes. Strikes occurred all over the country. In 1946, the railway strike gained momentum, leading to the arrest of seven trade union leaders. In response, workers initiated a strike. In Madras, 400 railway workers were arrested, and during a meeting, police firing resulted in the deaths of 9 people. In Ahmedabad, a strike was called in support of the South Indian Railways strikers, and by mid-September, over 1000 workers had been arrested.

In this manner, after the Second World War, various segments of the Indian population found themselves on the battleground. Workers, farmers, students, artisans, craftsmen, and small traders all fought against the British rulers, exploiters, and feudal lords in their own ways. Discontent spread among the Indian Army, Navy, and Air Force, setting the stage for national liberation.

Unfortunately, the movement’s leadership was in the hands of the reformist bourgeoisie. Instead of embracing revolution, they chose the path of negotiation and compromise, which the imperialist forces fully exploited.

Cabinet Mission

The naval strike began on February 18, 1946, and a day later, on February 19, 1946, British Prime Minister Attlee announced in the House of Commons that his government was dispatching a cabinet mission to India to address the Indian issue.

The mission’s members included the Secretary of State for India, Lord Pethick Lawrence; the President of the Board of Trade, Sir Stafford Cripps; and the First Lord of the Admiralty, A.V. Alexander. Attlee stated that the mission’s objective was “to make it possible, in cooperation with the leaders of Indian public opinion, to achieve complete self-rule in India at the earliest.” The mission had three main functions:

- Preliminary discussions with elected representatives of British India and princely states to facilitate consensus on establishing a constitution.

- Formation of a Constituent Assembly.

- Establishment of an executive council with support from major Indian parties.

Two key aspects of this statement garnered attention. Firstly, the word ‘independence’ was used for the first time in relation to India. Secondly, regarding minorities, it was stated, “We are fully alive to the minorities’ rights… Minorities should have nothing to fear… India must choose her own future constitution and her place in the world.”

While this British ruler’s statement was seen as a surprising shift in their policy toward India, it was noted by some that Attlee’s statement, despite using the word ‘independence,’ bore similarities to the 1942 Cripps Mission.

Amidst these discussions, elections for Central and Provincial Assemblies were held in April 1946. The results made it evident that while the Congress enjoyed overwhelming public support, the League had a majority of Muslim votes. This election outcome formed the basis for India’s partition.

The mission sought to showcase differences between political factions, especially the Congress and the League, by conducting separate talks with various parties and organizations. This effort led to the Shimla Conference, which concluded without reaching any decisions.

With differences between the Congress and the League and the election results, the British rulers seized the opportunity to make a unilateral decision. They imposed their decision on India, projecting a divide between the people and the Congress.

On May 16, 1946, the Mission, in consultation with the Viceroy and the British Cabinet, presented the following plan:

- Recommendation for future constitution:

(a) Establishment of an Indian federation, including the British government and princely states, with control over foreign affairs, defense, transport, and finances for these areas.

(b) Creation of a Union executive body and a Legislative Assembly comprising representatives from British India and princely states. Decisions on significant communal matters in the Legislature require a majority of present representatives and the votes of the two major communities (Congress and League).

(c) Provinces possess all subjects and residual powers, except those allocated to the Union.

(d) States retain all other subjects and powers, except those assigned to the Union.

(e) Provinces have the freedom to establish factions with their own executive and assembly.

(f) The Union and faction constitutions include a provision allowing any province to request a reevaluation of constitution clauses every ten years through a majority vote in its legislative assembly.

- Proposal for Constituent Assembly:

(a) Constituent Assembly with 389 members: 292 members from British Indian provinces, indirectly elected by current Legislative Assemblies based on communal representation, and 93 members from princely states. Seats for general, Muslim, and Sikh representation should be determined based on different populations.

(b) Division of provinces into three parts: (i) Hindu majority areas, (ii) Muslim majority north-west areas, (iii) North Eastern region with a Muslim majority. (c) There shall be an advisory committee for these areas. (d) The Constituent Assembly will decide the constitution of the Union.

- The basis of cooperation among the princely states will be determined through negotiation.

- A negotiating federation will be established between the Constituent Assembly for the British Indian Federation and the United States.

- An interim government should be formed by the Viceroy based on the reconstitution of the Executive Council.**

On May 16, 1946, Lord Wavell proposed forming an interim government based on the allocation of seats. Forty percent of seats would be given to Hindus, nominated by the Congress, and 40 percent to Muslims, nominated by the Muslim League. The remaining 20 percent would be distributed among Sikhs, Indian Christians, Scheduled Castes, and Parsis. Parties unwilling to join the interim government would be excluded.

Various opinions emerged regarding the Cabinet Mission. The British received considerable praise for it. Gandhi wrote in his publication ‘Harijan’, “The Cabinet Mission’s proposals contain the seeds that will make this country great, where suffering will have no place.” However, leftist factions strongly opposed this plan. The General Secretary of the Communist Party, Mr. P.C. Joshi, condemned the plan, stating, “It is Britain’s imperial strategy to retain India as its largest colonial base.”

Hence, the bourgeois leadership hailed this incident as a ‘glorious episode.’ Yet, on July 6, the Congress General Committee, chaired by Jawaharlal Nehru, accepted the Cabinet Mission’s plan but rejected the Interim Government’s plan. This stance didn’t sit well with the British rulers, who made it clear that either the entire plan should be accepted or rejected altogether.

On August 8, 1946, Congress fully endorsed the plan. Simultaneously, significant maneuvering took place in the economic sphere. Tata and Birla formed alliances, demanding cooperation in the political realm as well. After the Congress’s acceptance, the establishment of the Interim Government at the Center was announced on August 24, 1946. The members of the government were declared as follows: Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Mr. M. Asaf Ali, C. Rajagopalachari, Saratchandra Bose, Dr. John Mathai, Sardar Baldev Singh, Sir Shafaat Ahmad Khan, Jagjivanram, Syed Ali Johar, and Kawasji Hormusji Bhabha.

Both the Congress and the League participated in the Interim Government but faced internal conflicts. The Finance Department, in a bid to join the Provisional Government, demonstrated acrobatics. The presence of Congress’s Liaquat Ali complicated the Congress’s functioning. Additionally, the budget presentation posed challenges, intensifying the bitterness over time.

A conference took place in London from December 3-6, 1946, attended by British Prime Minister Attlee, Viceroy Wavell, Congress President Jawaharlal Nehru, and Muslim League President Mohammad Ali Jinnah. The royals boycotted the conference.

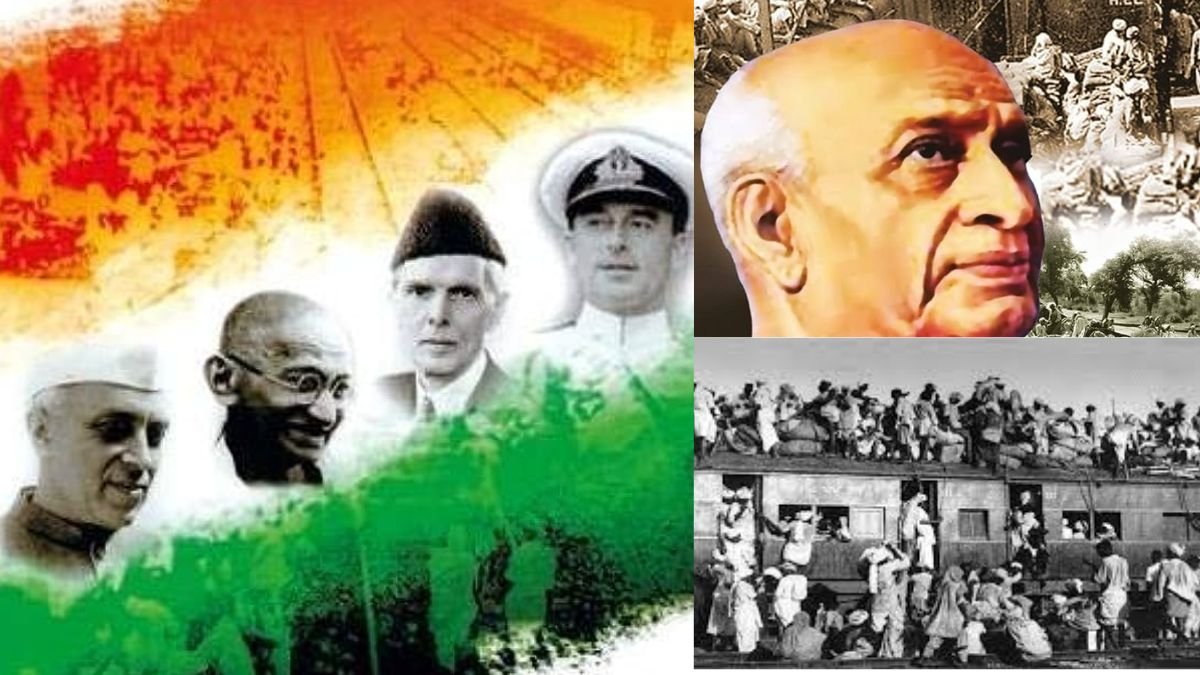

Mountbatten Plan and Partition of India

As the divide between Congress and League leaders deepened, and with the political situation rapidly deteriorating, the British government replaced Lord Wavell with Mountbatten as Viceroy.

A new plan emerged in the form of the Mountbatten Plan, with the following key points:

- India would be divided into two parts: the Indian Union and Pakistan.

- A plebiscite and vote would be held in the North-West Frontier Province and Sylhet district of Assam to determine which state they would like to join before finalizing the boundary between the two states.

- The demarcation of Punjab and Bengal needed resolution before India’s partition.

- After these matters were addressed, the Indian Constituent Assembly would split into two parts: the Constituent Assembly of the Union of India and the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. Both states would be granted dominion status.

- Princely states would have the right to choose which dominion to join. Those who wanted to join a Dominion would maintain their existing relations with Britain.

This plan aimed to divide India into two parts while allowing the princely states the freedom to choose, thereby preserving the British imperial base in India. The plan lacked a democratic Constituent Assembly elected through adult suffrage, and it fueled communalism, dividing India along feudal and communal lines.

In June 1947, after initial hesitance, Congress leaders accepted the plan, likely due to a lack of hope for an agreement with the Muslim League. Concurrently, communal tensions in the country were escalating, leading to violent riots. Some individuals who had advocated for Hindu-Muslim unity resisted accepting the plan.

Abul Kalam Azad commented, “Some ridiculous things were also witnessed during this great tragic drama. There have been some people in Congress who claim to be nationalists, yet their outlook has been communal for sixteen years.”

Indian Independence Bill – July 4, 1947

On July 4, 1947, the Indian Independence Bill was introduced in the British Parliament. It was passed by the House of Commons on July 15 without any amendment and by the House of Lords on July 16. On July 18, the British Emperor signed it, and it was announced that from August 15, 1947, India would be divided into two entities.

On August 14th, the Dominion of Pakistan would be established, and on August 15th, the Dominion of India. As the clock struck midnight on August 14 and ushered in August 15, Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, while addressing the Constituent Assembly, said:

“At this midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India shall wake up to life and liberty. It is fitting that at this solemn moment, we take the pledge of dedication to India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity.”

Partition: Cost and Process

Partition shattered the political unity of the Indian people. Could the public truly accept it wholeheartedly? Abul Kalam Azad wrote, “The Congress and the League accepted the Partition. When we looked before and after the partition of the country, we realized that this approval was only on paper, through the resolutions of the Congress General Committee and the register of the Muslim League. They did not truly embrace it. In reality, their hearts and souls rebelled against this idea.”

This division occurred on religious lines, triggering intense communal conflicts fueled by reactionary forces. Hundreds of thousands of Hindus and Muslims were uprooted from their ancestral lands. Within forty-eight hours, reports emerged of violent communal riots in East Punjab and West Punjab, followed by Delhi and Karachi – no one was spared from this turmoil.

With the division of the armed forces, communalism found its way within. Detailing these incidents is challenging, but according to Bhonsle, a friend of Nehru and the author of his biography, around 600,000 people were killed in Punjab alone, and 14 million became refugees. Both sides abducted and forcibly converted around 100,000 young women into housewives.

Starting from January 12, 1948, Gandhi began fasting. Patel left him in this state and traveled to Bombay. When asked to end his fast, he replied, “What’s the use of stopping?” Tragically, Gandhi was assassinated on January 30, 1948, and India lost a significant leader of the liberation movement due to the course taken by the bourgeois leadership.

Thus ended a chapter of the Indian revolution – the united front of all classes against imperialism. Workers, peasants, and the middle class together uprooted the imperialist influence.