The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, commonly referred to as the Amritsar Massacre, occurred on b, as a harrowing incident characterized by the severe actions of General Dyer. In this infamous event, General Dyer ordered the indiscriminate firing upon an unarmed assembly of men, women, and children who found themselves confined within the walls of an abandoned garden during a Sikh festival. The tragic consequences of this brutal incident resulted in a staggering loss of life, with a minimum of 379 fatalities and over 1,500 individuals sustaining injuries.

Context of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre:

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre unfolded against the backdrop of intense riots that gripped Punjab and other regions in April 1919. Amritsar slipped from British control on April 11, prompting the Governor of Bengal to dispatch General Dyer to restore order. Unyielding in his actions, Dyer believed he had employed necessary force to quell the civil unrest, marked by the murder of five Europeans.

Despite the subsequent inquiry into the horrific massacre, Dyer remained unapologetic, asserting that he had averted further escalation. The aftermath saw Dyer being dismissed from the army. This tragic event stands as one of the most infamous episodes, arguably the zenith of British colonial rule in India’s tumultuous history.

Historical Context: The British Raj in India

The onset of the British Raj in India dates back to 1858, marking the transfer of control from the British East India Company (EIC) to the British Crown and State. This transition occurred in the aftermath of the EIC’s final act, suppressing the tumultuous Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-58, a bloody rebellion against colonial rule.

The violent episodes during the Sepoy Mutiny left a lasting impact, particularly on the British, fostering a lingering apprehension of potential uprisings. The British administration found itself presiding over a far-from-unified India, marked by intricate divisions. Political maps illustrated the diverse relationships of Indian princely states, varying degrees of dependence or neutrality.

Religious distinctions played a pivotal role, with Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs forming the three major religious segments. Additionally, the caste system and significant economic disparities among regions and communities underscored the intricate fabric of Indian society. The colonial division was not absolute, as many Indians found employment in the British Indian Army and civil service.

Maintaining control over this complex cultural amalgamation presented a formidable challenge for the British Empire. India, often referred to as the “jewel in the crown” of British imperialism, required delicate maneuvering to exploit its resources without inciting open rebellion. The British Raj in India encapsulated a precarious balance, symbolizing the intricate dance between exploitation and control in the vast and diverse landscape of the Indian subcontinent.

Seeds of Indian Political Awakening

The specter of potential uprisings became a fixation for numerous staunch British officials, fueled by indications that Indians were increasingly embracing the idea of concerted and unified political action. The Indian National Congress, established in 1885, and the All India Muslim League, formed in 1906, served as noteworthy symbols of burgeoning political consciousness.

The contentious partition of Bengal in 1905 triggered widespread nationalist outrage, an outcry that eventually led to its reversal in 1911. The first decade of the 20th century witnessed the development of mass-based politics, with a growing number of Indians challenging the British presence in the subcontinent.

A pivotal moment in this political evolution occurred in 1916 when the Congress and Muslim League joined forces through the Lucknow Pact. This landmark agreement outlined what was deemed essential constitutional reforms, paving the way for the envisaged establishment of an independent Indian government. The collaboration reflected a significant shift in the dynamics of Indian political discourse and set the stage for future developments in the quest for self-determination.

Escalation of Colonial Tensions during the First World War and the Rowlatt Acts

The colonial tensions in India reached a critical juncture during the First World War (1914-18), exacerbating an already strained relationship. Indian soldiers had valiantly fought to protect British interests both in India and overseas, yet upon their return, many faced unemployment. The significant contribution of India in terms of equipment and raw materials for the war effort underscored the shortcomings of the British administration.

The Punjab region, perceived as a particularly precarious zone for British interests, stood out due to the unity and political activism of Indians from various faiths, exemplified by groups like the Ghadar party, committed to expelling the British from India.

The turning point came with the March 1919 enactment of the Rowlatt Acts. These acts granted the British administration extended powers of control and imprisonment, previously used to suppress protests during the World War. Indians found themselves subject to imprisonment without cause, trial without a jury, and degrading forms of punishment. Responding to this oppressive legislation, Mahatma Gandhi, a central figure in the Indian independence movement, called for a suspension of work as a form of peaceful civil disobedience on April 8.

Despite widespread adherence to Gandhi’s call, the British authorities remained resolute, refusing to repeal the Rowlatt Acts. The ensuing unrest led to riots, arson attacks, lootings, and clashes with the police, notably in Amritsar, where a mob killed five British men on April 10. Similar episodes of unrest unfolded in Delhi and Ahmadabad. Gandhi’s subsequent arrest did little to quell the agitation. In response to the mounting turmoil, all forms of public gatherings were prohibited. The events of this period marked a pivotal chapter in the intensifying struggle for Indian self-determination.

General Dyer: A Controversial Figure in the Indian Colonial Landscape

Brigadier-General Reginald Edward Harry Dyer, born in India to Irish parents in 1864 and passing away in 1927, emerged as a prominent figure in the British Indian Army. Having served in Persia, his career had been marked by questionable decision-making, notably expanding British territory without orders. His actions in Persia were spared censure only due to ill health, allowing him to be transferred back to India.

In 1919, at the age of 55 and nearing the end of his career, Dyer assumed command of the 45th Brigade of the British Indian Army in Jalandhar. His return to India coincided with rising tensions, and his leadership would soon be put to the test in the volatile atmosphere of post-World War I India.

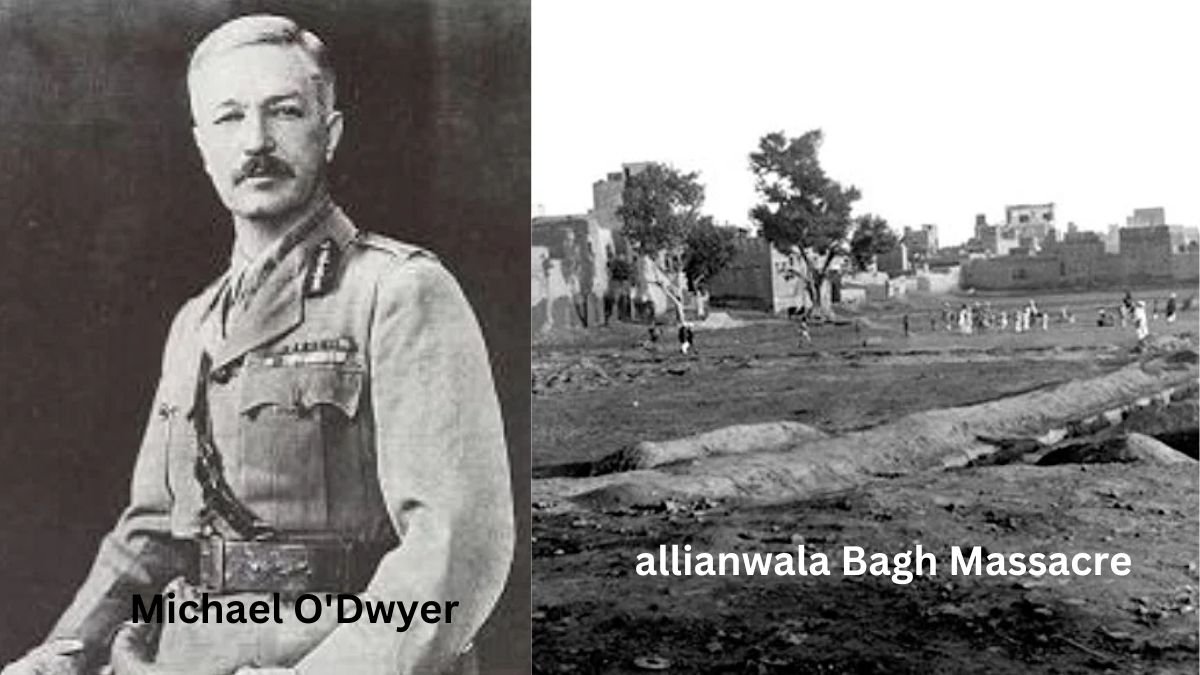

Governor of the Punjab, Sir Michael O’Dwyer, displayed a lack of sympathy towards Indian aspirations for self-governance. O’Dwyer, known for ordering the use of aircraft against rioters, shared a pervasive paranoia with figures like Dyer. Both were determined to prevent a recurrence of the 1857-58 Sepoy Mutiny and contended with persistent rumors suggesting Soviet Russia’s alleged support for Indian nationalists to destabilize the British Raj.

Faced with escalating unrest in Amritsar, triggered by the arrest of two prominent Indian nationalists on April 10, O’Dwyer directed Dyer to quell the riots. The subsequent events, including Dyer’s infamous actions in Jallianwala Bagh, would etch his name into the annals of history, encapsulating the controversial role played by key figures during a critical period in India’s struggle for independence.

Upon his arrival in Amritsar on April 11, General Dyer confronted the aftermath of violent riots that had engulfed the city. The scenes included the looting and burning of two banks and two mission schools. Europeans had fallen victim to the violence, with several killed, and a female European doctor subjected to a brutal beating. Faced with a loss of control, other Europeans sought refuge in the Gobindgath fort, emphasizing the severity of the situation in a city with a population of 150,000.

On April 12, Dyer took a proactive stance, mobilizing 400 men and two armored cars mounted with machine guns for a conspicuous display of force through the streets of Amritsar. Despite the imposing show of strength, the day passed without further violence. However, Dyer remained vigilant as reports suggested ongoing riots in other Indian cities, coupled with rumors that cast doubt on the loyalty of his Indian troops.

The morning of April 13 witnessed Dyer’s decisive actions. Notices were distributed throughout the city proclaiming an immediate ban on all public meetings, processions, and gatherings. Additionally, a curfew was slated to begin at 8 pm. The reading of these notices was met with defiant shouts, signaling a sentiment that the British Raj was over. Dyer, now aware of a planned gathering in open defiance of his orders, grappled with the conviction that a forceful demonstration was necessary to reassert British control over Amritsar.

Tragedy Unfolds at Jallianwala Bagh: A Peaceful Gathering Turns Nightmare

On the fateful afternoon of April 13, a multitude of 15-20,000 Indian civilians congregated in the Jallianwala Bagh, an abandoned walled garden in Amritsar. The location, with only five narrow entrances, became a space where diverse motives converged. Many were there to peacefully celebrate the Sikh Baisakh festival and partake in the accompanying fair. Some gathered to protest the recent imprisonment of nationalists, while others were merely passing through, given its status as a major thoroughfare and the site of the Golden Temple, an important Sikh temple.

The garden, despite being a sort of wasteland, provided a vast open space suitable for such a large assembly. Moreover, it’s plausible that many in the crowd were unaware of Dyer’s morning announcements, particularly those who came from outside Amritsar. The presence of a British plane flying overhead convinced some attendees to disperse.

At 5 pm, General Dyer arrived at Jallianwala Bagh with his two armored cars and approximately 90 men, primarily Gurkhas and Indian troops. Due to the narrow gateway, only infantry could enter. Without warning, Dyer ordered his men to open fire on the unarmed crowd and persist until instructed otherwise.

The ruthless firing, lasting around ten minutes, allowed the soldiers to reload their magazines. A total of 1,650 shots were discharged, with specific orders to target those attempting to escape over the high walls or through the doorways. After the bloodshed, Dyer ordered his men to leave, offering no assistance to the wounded.

Official figures reported 379 deaths and over 1,500 injuries, but the actual toll might have been much higher. In the aftermath, Dyer sanctioned public floggings of Indian prisoners and subjected any Indian man present in Kucha Kurrichhan street to crawl on the pavement in a humiliating public display. Martial law was declared in the Punjab, with O’Dwyer authorizing aircraft to bomb rioters at Gujranwala. The ensuing months witnessed continued police brutality, resulting in 1,200 deaths, 3,600 injuries, and 258 public floggings, leaving an indelible mark on the tragic events at Jallianwala Bagh.

Mixed Reactions and Reckoning

The reaction to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre was nuanced, with many Britishers, including Viceroy Lord Chelmsford, believing that the actions of O’Dwyer and Dyer had prevented the unrest from spreading and escalating further in the Punjab. Some saw them as crucial in maintaining control. However, dissenting voices emerged, and their chorus grew louder after the news blackout accompanying martial law ended in June. The events were momentarily overshadowed by a war on the Afghan frontier in which Dyer participated.

The reckoning finally arrived in November 1920 when a committee appointed by the British government, led by Lord Hunter, conducted a public hearing in Lahore. The committee, consisting of four British and three Indian members, cross-examined Dyer. His admission that he would have used armored cars if possible did him no favors. Unrepentant, Dyer justified his actions as the necessary means to prevent rebellion, aiming to produce a “moral and widespread effect” against dissent.

The committee concluded that Dyer’s judgment was tainted by racism and, possibly, mental illness. Despite the acknowledgment of excessive force, both Dyer and O’Dwyer received only reprimands from the Hunter Committee. The British members insisted that a degree of force was necessary to preserve control in India. However, far from settling matters, the committee’s findings fueled ongoing outrage. Viceroy Chelmsford, initially supportive, changed his stance, advising King George V that Dyer should not be hailed as a heroic defender of the British Empire. Dyer was granted six months’ leave and returned to England, but the repercussions of the massacre continued to reverberate.

Amritsar Massacre’s Impact on the Indian Independence Movement

The revelation of General Dyer’s ruthless conduct and subsequent unapologetic stance sent shockwaves through the British establishment in London. Legislators, cognizant of the limitations of ruling solely through force, grappled with understanding the motivations behind the general’s actions. Dyer himself, when confronted by a journalist in England, defended his decision: “I had to shoot. I had thirty seconds to make up my mind what action to take, and I did it. Every Englishman I have met in India approved the act, horrible as it was” (James, 478).

Despite the House of Lords voting in Dyer’s favor, the public tide was turning against him, prompting orders for his resignation from the army and strong encouragement to retire. Surprisingly, the British press largely supported Dyer, with The Morning Post even initiating a fund for him. This fund garnered remarkable popularity, drawing contributions from various individuals, including Northumberland farmers and the esteemed author Rudyard Kipling. Many believed that Dyer, in an unusual display of decisiveness, had acted to protect the British Empire. They argued that he had been unfairly singled out by bureaucrats who were detached from the realities of colonial circumstances on the ground. According to this narrative, Dyer was not the villain but the savior of the empire.

In stark contrast, the British government, acknowledging the victims’ families, eventually awarded each of them a meager £37 ($1600). This stark divide in financial support further underscored the complex and conflicted responses within British society to the tragic events at Jallianwala Bagh.

Legacy of Jallianwala Bagh: Unraveling Imperial Morality

The reverberations of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre echoed loudly in the hearts of Indians, fueling a sustained wave of outrage. The renowned Bengali author Rabindranath Tagore, deeply appalled, even renounced his knighthood in protest. Surprisingly, even some pro-British rulers of independent princely states, like the Raja of Nabha, voiced their disapproval of Dyer’s excessive use of force.

The shocking pension bestowed upon Dyer served as a grotesque reward, intensifying the indignation among Indians, who could no longer dismiss the events as the actions of a rogue soldier exceeding orders. Jawaharlal Nehru, the future prime minister of India, encapsulated the sentiment, stating, “I realized then, more vividly than I had ever done before, how brutal and immoral imperialism was and how it had eaten into the souls of the British upper classes” (Tharoor, 173).

The failure of the Hunter Committee to hold anyone accountable for the evident violence and acts of humiliation in Punjab in 1919 underscored the whitewashing of history by the British administration. Above all, the non-cooperation movement led by Gandhi found a broader base of support from 1920 onward, pushing relentlessly for ‘home rule.’

Indians across social classes actively contributed to convincing Britain, by any means necessary, to grant independence—an accomplishment realized in 1947. Historian S. Mansingh aptly notes, “Jallianwala Bagh became the beginning of the end of British rule in India” (201). The atrocity etched a powerful chapter in India’s struggle for independence, exposing the moral decay within imperialist structures and galvanizing a collective pursuit of freedom.

FAQS

Q: When did the Jallianwala Bagh massacre occur?

Ans: The Jallianwala Bagh massacre took place on April 13, 1919.

Q: Who was the British general responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre?

Ans: Brigadier-General Reginald Edward Harry Dyer led the troops during the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

Q: How many people were killed in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre?

Ans: Officially, 379 people were reported dead, but the actual toll might have been higher.

Q: What led to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre?

Ans: The massacre was triggered by General Dyer’s orders to open fire on a peaceful gathering in Amritsar during the Sikh Baisakh festival.

Q: Did the British government take action against General Dyer?

Ans: General Dyer was reprimanded and ordered to resign from the army, but he received support from some British quarters.

Q: How did the Indian Independence movement respond to the massacre?

Ans: The massacre intensified support for the Indian Independence movement, strengthening the call for self-governance.

Q: Did the Hunter Committee find anyone guilty of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre?

Ans: The Hunter Committee failed to find anyone guilty, raising concerns about the whitewashing of history by the British administration.

Q: What was the impact of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre on Rabindranath Tagore?

Ans: Rabindranath Tagore, deeply disturbed by the massacre, renounced his knighthood in protest.

Q: How did the Jallianwala Bagh massacre influence Jawaharlal Nehru’s views?

Ans: Nehru stated that the event heightened his realization of the brutality of imperialism and its impact on the British upper classes.

Q: What is the significance of Jallianwala Bagh in Indian history?

Ans: Jallianwala Bagh is considered the beginning of the end of British rule in India, leaving an indelible mark on the struggle for independence.