A Sikh-era field in Amritsar, East Punjab, India, where British forces opened fire on an unarmed crowd on April 13, 1919. The reason for this massacre was the enactment of the controversial Rowlatt Act on March 21, 1919, through which the freedom of Indians was taken away. The Act was being opposed by demonstrations and hartals across the country and Amritsar was also in a state of rebellion.

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar Massacre, took place on April 13, 1919, when a peaceful protest was suddenly opened fire by the British Indian Army on the orders of General Dyer. The demonstration also included those involved in the Baisakhi fair, which had gathered at Jallianwala Bagh in Punjab’s Amritsar district. These people participated in the Baisakhi festival which is a festival of cultural and religious significance for Punjabis. The visitors to the Baisakhi fair had come from outside the city and were not aware that martial law was in force in the city.

At 15:15 General Dyer arrived there with fifty soldiers and two armored vehicles and without any warning ordered to open fire on the crowd. This order was obeyed and hundreds lost their lives within minutes.

The area of this ground was 6 to 7 acres and it had five gates. On Dyer’s orders, the sepoys opened fire on the crowd for ten minutes and most of the bullets were aimed at people coming out of those same gates. The British government put the number of dead at 379 and the number of injured at 1,200. Other sources put the total death toll at over 1,000. This massacre shook the entire country and they lost faith in British rule. After a flawed initial investigation, Dyer’s comments in the House of Lords fueled the fire and the Non-Cooperation Movement began.

Activities before the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

On Sunday, April 13, 1919, when Dyer came to know about the agitators, he banned all gatherings, but the people did not listen to him. As the day of Baisakhi holds religious significance for Sikhism, people from nearby villages gather on the ground.

When Dyer came to know about the crowd in the ground, he immediately took fifty Gurkha soldiers with him and posted them on an elevated position at the edge of the garden, and ordered them to fire on the crowd. The gunfire lasted for about ten minutes until the bullets were almost over.

Dyer said that a total of 1650 bullets were fired. This number may have been derived from counting the empty cartridges of bullets collected by the jawans. According to British Indian officials, 379 were declared dead and around 1,100 were injured. According to the Indian National Congress, the death toll was estimated at 1,000, and the number of injured was around 1,500.

Appreciation of the work filed by the British Government

At first, Dyer was highly praised by British conservatives, but by July 1920, the House of Representatives had voted him out of the office and retired. In Britain, Dyer was hailed as a hero by monarchists such as the House of Lords, but disliked by democratic institutions such as the House of Representatives, and twice voted against.

After the massacre, the military’s role was redefined as a minimal force, and the military adopted new drills and new methods of crowd control. According to some historians, this event sealed the fate of British rule, while others believe that India’s involvement in World War I was a sign of independence.

Background of Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

Defense of India Act

During World War I, British India contributed manpower and money to the battlefield for Great Britain. 1,250,000 soldiers and laborers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, while the Indian administration and rulers provided food, money, and weapons. However, agitations against British colonialism continued in Bengal and Punjab.

The revolutionary attacks in Bengal and Punjab almost paralyzed the local administration. Among them, the most important was the February 1915 mutiny plan of the British Indian Army, which was one of the mutiny plans made from 1914 to 1917. The proposed coup was suppressed by the British government, after infiltrating its spies into rebel groups and arresting prominent pro-independence rebels.

The rebels, found in small detachments and outposts, were crushed. In this situation, the British government passed the Defense of India Act of 1915 under which political and civil liberties were restricted. Michael O’Dwyer, who was then the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, was very active in getting the Act passed.

What was the Rowlatt Act?

The cost and casualties of the long war (World War I) were high. There was no end to the hardships of the people of India due to high death rates and rising inflation rates and heavy taxes, the influenza pandemic of 1918, and the suspension of trade during the war. Prior to the war, Indian nationalist sentiment was fueled by moderate and extremist factions of the Indian National Congress and united over their differences.

In 1916, Congress passed the Lucknow Pact, which forged their temporary alliance with the All-India Muslim League. British politics and Whitehall’s India policy also began to change after World War I, and the Motago-Chelmsford Reforms in 1917 began the process of political reform in the subcontinent. However, Indian political parties considered this to be insufficient.

Mahatma Gandhi, who had recently come to India from South Africa, began to emphasize his charismatic personality and political importance. The Non-Cooperation Movement began under his leadership and soon political unrest spread across the country.

A committee was formed in 1918 under the chairmanship of an English judge named Sidney Rowlatt due to the rebellion crushed some time ago, Mahendra Pratap’s presence in the Kabul mission in Afghanistan, and the ongoing agitations in Punjab and Bengal. His task was to investigate possible German and Bolshevik links to the ongoing movements in India. On the recommendations of the committee, the Rowlatt Act was passed, which was a comprehensive version of the Defense of India Act of 1915. This further restricted Indian civil liberties.

Opposition to Rowlatt Act

Following the passage of the Rowlatt Act in 1919, widespread unrest broke out across India. Incidentally, the Third Afghan War began in 1919, as a result of the assassination of Amir Habibullah. Also, Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement received a very positive response from all over India. The situation, particularly in Punjab, was rapidly deteriorating and rail, telegraph, and other means of communication were being cut off.

The protest reached its peak in the first week of April and according to some sources the whole of Lahore took to the streets. More than 20 thousand people gathered in Anarkali. More than 5,000 people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar. The situation worsened over the next several days.

According to Michael O’Dwyer, another rebellion like that of 1857 was looming large. It was expected that the rebellion would begin in May when the British army moved to the highlands due to the heat. The Amritsar Massacre and the events before and after it proved that it was a plan by the government to suppress the rebellion.

Conditions before the genocide

Many British Indian military officers believed that a mutiny was likely. 15,000 people gathered at Jallianwale Bagh in Amritsar. Michael O’Dwyer, the British lieutenant governor of Punjab, is said to have believed that these were early signs of an insurrection, which was due to begin in May. Due to the scorching heat in the month of May, the British soldiers used to go to the hilly areas.

According to some historians, government orders before and after the Amritsar massacre make it clear that it was an attempt by the Punjab administration to suppress the rebellion. According to James Hausman du Boulay, this massacre was the result of the steps taken by the government in view of the apprehension of rebellion in Punjab and the tense situation there.

On April 10, 1919, a protest was held outside the residence of the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar. Punjab was a large province in northwestern India. The purpose of the demonstration was to demand the freedom of Dr. Satya Pal and Dr. Saifuddin Kuchlu, two popular leaders of India’s freedom movement. He was arrested some time ago and transferred to a secret location. Both leaders were supporters of the Satyagraha movement started by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

A military front opened fire on the crowd, killing hundreds of protesters, and violence broke out. Later that day, several banks and other government buildings were attacked and set on fire, including the town hall and railway station. Violence escalated and five Europeans were killed, including government employees and civilians. The army opened fire on the protesters several times during the day, and between 8 and 20 protesters were killed that day.

On 11 April, Miss Marcella Sherwood, an English missionary, concerned about the safety of her students, closed her school and sent home over 600 Indian students. However, he was caught by a mob while cycling down a narrow road called Kacha Krichchan, and after being dragged by the hair and thrown to the ground, forcibly stripped of his clothes, tortured, and then left for dead. The father of one of his students and other local people helped him, picked him up and took him to a safe place hidden from the crowd and then he was secretly taken to Gobindgarh Fort.

After a meeting with Sherwood on 19 April, Colonel Dyer, the local commander of the British Raj, issued an order that every Indian male crossing the above road must do so on hands and knees. Colonel Dyer later explained to a British inspector: ‘Some Indians prostrate or prostrate themselves before their gods. I want to show them that the British woman is as blessed as their God and they should bow down before her.” The person should be flogged in a public place. Miss Marcellus Sherwood later defended General Dyer, calling him the savior of Punjab.

For the next two days, the city of Amritsar remained calm, but rioting continued in other parts of Punjab. Railway lines were uprooted, telephone poles were uprooted, government buildings were set on fire, and three Europeans were killed. On 13 April, the British government decided to impose martial law on most of Punjab. Most civil liberties were curtailed under the law and gatherings of more than 4 people were prohibited.

On the evening of 12 April in Amritsar, the strike leaders held a meeting at the Hindu College, Dhab Khatekan, where Dr. Saifuddin Kuchlu’s advisor Hans Raj announced a public demonstration at Jallianwala Bagh at 4:30 pm the next day. Day. Its management was entrusted to Dr. Muhammad Basheer and it was presided over by senior Congress leader Lal Kanhaiyalal Bhatia. The Rowlatt Act and recent British actions against and the release of Dr. Satyapal and Dr. Saifuddin Kuchlu were also demanded. After this, the meeting ended.

Jallianwala Massacre Massacre

On the morning of 13 April, the traditional festival of Baisakhi began and Colonel Dyer, as military commander of Amritsar, patrolled the city along with other city officials and ordered to obtain permits for entry and exit from the city and also That there would be a curfew starting at 8 p.m. and all public gatherings and gatherings of four or more people would be banned.

The proclamation was read out in English, Urdu, Hindi, and Punjabi, but subsequent events showed that few people heard or understood it. Meanwhile, the local secret police learned that there would be a public meeting at Jallianwala Bagh. Dyer was informed of this at 12:40 and returned to his headquarters at half past one to prepare to deal with the gathering.

By noon thousands of Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus had gathered at Harmandar Sahib in Jallianwala Bagh. Many people had come to worship in the Golden Temple and were going to their homes through the garden. The garden is an open area spread over an area of six or seven acres. This area is about two hundred yards long and two hundred yards wide and is surrounded by four walls about ten feet high.

The balconies of the houses are three or four storeys above the ground and overlook the garden. There are a total of five narrow entrances to the garden, many of which were locked. Crops were also grown here during the rainy season, but for most of the year, their work was confined to playgrounds and public meetings. There was a samadhi (cremation ground) in the middle of the garden and a twenty feet wide water well was also situated.

Apart from the pilgrims coming for the annual Baisakhi Cattle Fair, there was a gathering of farmers, traders, and shopkeepers in Amritsar for the past several days. The city police closed down the fair at 2 am, and as a result of which many people moved to Jallianwala Bagh.

It is estimated that at that time twenty-five to twenty-five thousand people were gathered in the garden. Dyer sent an airplane to assess the number of people in the garden. By this time the head of the city administration, Colonel Dyer, and Deputy Commissioner Irving were aware of the meeting but made no attempt to stop it or to remove it peacefully by the police. Dyer and Irving were later criticized for

The time of gathering was half past four and an hour later Colonel Dyer reached the Bagh with a total of 90 Gorkha soldiers. 50 of them had three—not three—Lee Enfield bolt-action rifles. Forty had long Gurkha knives. It is not known whether the Gurkha soldiers were chosen because of their unwavering loyalty to the British government or whether non-Sikh soldiers were not available at that time.

In addition, two armored vehicles equipped with machine guns were also brought along, but these vehicles were left outside because the paths of the garden were too narrow and the vehicles could not enter. There were residential houses in all directions around Jallianwala Bagh. The main entrance was relatively wide and behind it was guarded by soldiers in armored vehicles.

Dyer neither warned the crowd nor asked them to end the meeting and closed the main entrances. He later said, “My object was not to destroy the assembly but to punish the Indians”. Dyer ordered the soldiers to fire at the most congested parts of the crowd. The firing was stopped when the ammunition was almost exhausted and an estimated 1650 rounds were fired.

Many died in a stampede in the narrow streets trying to escape the firing, and others died by jumping into wells. According to the plaque on the well after independence, 120 dead bodies were removed from this well. Even the injured were not allowed to be lifted as curfew was in force. Many of the injured also died in the night.

The number of casualties from the firing is unclear. The official figures of the British investigation put the total death toll at 379, but objections were raised to the method of this investigation. In July 1919, three months after the massacre, authorities called on people in the area to volunteer information about the victims in order to identify the victims.

However, many people have not come forward to prove that they were also involved in this illegal gathering. Moreover, many close relatives of the deceased were not from this city. Talking to the members of the committee, according to a senior official, the death toll could be many times more.

As official estimates of the size of the crowd, the number of firings, and its duration could be inaccurate, the Indian National Congress set up another inquiry committee of its own, which came out with results that differed greatly from the official findings.

A congressional committee estimated the number of injured at over 1,500 and the death toll at 1,000. The government tried to hide the news of this massacre, but this news spread all over India and anger spread among the people. The news of this massacre reached Britain in December 1919.

Effect

Colonel Dyer told his superiors that he was facing “armed rebels”, to which Major General William Bannon replied “Your action was correct and the Lieutenant Governor has approved it”. O’Dwyer recommended the imposition of martial law on Amritsar and the Viceroy Lord Chelmsford approved it.

The then War Secretary Winston Churchill and former Prime Minister HH Asquith publicly condemned the attack. Churchill called it “horrible” while Asquith called it “one of the worst incidents in our history”.

On July 8, 1920, Churchill said in the House of Commons, “The mob was furious and they had sticks.” He didn’t attack anyone. When bullets were fired at them, people tried to run away. There was such a large crowd in a space smaller than Trafalgar Square, and shots were fired into the crowd. When he tried to escape, he had no way out.

People were so close to each other that one bullet probably hit three or four people. People were running hither and thither like madmen to save their lives. Then shots were fired on the sides as well. The whole incident came to a halt after eight-ten minutes when the gunfire was about to end. In a vote held after Churchill’s speech, the Members of Parliament voted 247 against General Dyer and 37 in favor.

Rabindran Singh Tagore was informed of the massacre on 22 May 1919. He attempted a protest in Calcutta and eventually returned the title of ‘Sir’ in protest. In a letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, dated May 30, 1919, Tagore wrote: ‘I wish to put aside all honor and stand by my countrymen, who suffer from their so-called inferiority complex and are deprived of being called human.

According to Gupta, Tagore’s letter has ‘historical’ significance. He wrote: “Tagore returned his title of ‘Sir’ and thus expressed his protest against the inhuman treatment meted out to the people of Punjab by the British Government.” In his letter to the Viceroy, Tagore pointed out how the British government’s inhuman attitude towards local unrest and massacres reflected its disregard for the life and property of the Indian people. Tagore also wrote that it was his duty to return all British honors in solidarity with the plight of his countrymen.

According to Cloak, although the incident was officially condemned, many Britons hailed him as a “hero for defending British law”.

Hunter commission

In October 1919, Secretary of State for India Edwin Montagu ordered that a committee be set up to investigate the incident. This commission was later called Hunter Commission after the name of the head of the commission. Lord William Hunter was a former Solicitor General for Scotland and a Senator of the College of Justice of Scotland.

The aims and objectives of the commission were: ‘to inquire into the recent incidents of unrest in Bombay and Punjab, to ascertain their causes and to review the measures taken to deal with them’. The members of the commission were:

- Lord Hunter, Chairman of the Commission

- Mr. Justice George C. Rankin of Calcutta

- Sir Chamanlal Harilal Setwald, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Bombay and Advocate of the Bombay High Court

- Mr. W.F. Rice, Member of the Home Department

- Major General Sir George Barrow, KCB, KCMG, GOC Peshawar Division

- Pandit Jagat Narayan, lawyer and member of the United Nations Legislative Council

- Mr. Thomas Smith, Member of the Legislative Council of the United States of America

- Sardar Sahibzada Sultan Ahmed Khan, an advocate of the princely state of Gwalior

- Mr. H.C. Stokes, Secretary to the Commission and Member of the Home Department

After meeting in New Delhi in October, the commission recorded eyewitness statements over the coming weeks. Witnesses were called in Delhi, Ahmedabad, Bombay, and Lahore. Although the commission was not appointed by the Constitutional Court and witnesses were not required to take oaths, members of the commission took detailed information through repeated questioning. The general feeling was that the commission had done its job very well. On arriving in Lahore in November, the commission completed its preliminary investigation and focused on primary witnesses to the events in Amritsar.

The commission summoned Dyer on 19 November. Although Dyer had been advised by his superiors to appear with legal counsel, he preferred to go it alone. Initially questioned by Lord Hunter, Dyer replied that he had learned about the meeting at Jallianwala Bagh at 12:40 and had made no attempt to prevent it. He said that he had gone to the garden with the intention of shooting at the crowd.

Speaking of his self-esteem, Dyer said, ‘I think the mob could have been dispersed easily, but then they would come back and make fun of me and I would feel like a fool.’ Dyer later reiterated that he believed the mob in the garden were rebels trying to cut him off from his troops and supply lines. So he felt his responsibility and was fired.

After Mr. Justice Rankin, Sir Chimanlal asked Dyer:

Sir Chamanlal: Suppose the entrance to the garden is wide enough for an armored vehicle to pass through, would you?

Shooting with a machine gun?

Dyer: I think so.

Sir Chamanlal: In this way, the loss of life would have been much more?

Dyer: Yes.

Dyer also said that in this way his intention was to create a wave of terror in Punjab and demoralize the rebels. He said that he did not stop firing when the crowd dispersed, as it was his duty to keep firing till the crowd dispersed. Light firing is of no use. He kept on firing till the bullets ran out. After firing, he clearly said about saving the lives of the injured: ‘It was not my duty to save their lives. Had the hospital been open, he would have gone to the hospital.

Due to fatigue and illness from the barrage of questions from the commission, Dyer was let go by the commission. Over the next several months, the commission continued to write its final report, during which time the British media and many members of parliament began to oppose Dyer, who by then had reached Britain in detail.

Lord Chelmsford declined to comment pending the commission’s report. Meanwhile, Dyer was hospitalized with jaundice and narrowing of the arteries. Although the members of the commission were divided by their ethnic affiliation and the Indian members wrote their reports separately, the final report consisted of six volumes of witness statements and was issued on March 8, 1920, and unanimously endorsed Dyer. condemned the actions of It was clearly written that ‘as long as General Dyer kept firing, it was a fatal mistake’.

Opposition members insisted that the use of force by the government during martial law was completely wrong. The report stated that “although General Dyer thought he had suppressed the rebellion and Sir Michael O’Dwyer was of the same opinion, there was no rebellion and there was no need to crush it”. The report concluded:

- It was a mistake not to order the crowd to disperse at the outset

- The firing Period Was Another Fatal Error

- Dyer’s views on firing are reprehensible

- Dyer violated his authority

- There was no conspiracy against British rule in Punjab

The Indian members of the commission further wrote:

The ban on public gatherings was not properly announced

There were innocent citizens in the crowd who had never rioted in the garden before

Dyer should have either ordered the soldiers to help the wounded or sent orders to the civil authorities

Dyer’s actions were highly inhuman and un-British and badly damaged the image of the British Government in India

The Hunter Commission did not recommend any departmental action or criminal prosecution against Dyer as his superiors condemned Dyer’s action and were later supported by the Army Council. The legal and home members of the Viceroy’s Council concluded that Dyer’s act was barbaric and cruel.

But legal or military action cannot be taken against him for political reasons. He was finally removed from his post on 23 March after being found guilty of dereliction of duty. He was recommended for a CBE for his services during the Third Afghan War, but the recommendation was withdrawn on 29 March 1920.

Protest in gujranwala

Two days later, on 15 April, a protest against the Amritsar massacre was held in Gujranwala. Police and aircraft were used against the protesters, resulting in 12 deaths and 27 injuries. Brigadier General NDK MacEwan, commander of the British Imperial Army in India, later said:

I think we have been very helpful in ending the recent protests, especially in Gujranwala, if it was not for the bombs and Lewis guns with the help of an aircraft, the protest would have been much worse.

Michael O’Dwyer was murdered by Udham Singh

Michael O’Dwyer was shot dead by Udham Singh at Caxton Hall in London on March 13, 1940. Udham Singh was an eyewitness to the Amritsar incident and was also injured in the firing that day. Michael O’Dwyer was the British Lieutenant Governor of Punjab at that time and not only supported Dyer but is also believed to have drawn up the original plan. Dyer died in 1927.

Nationalist newspapers like Amrit Bazar Patrika ran positive news about it. The works of Adham Singh were praised by the people and the revolutionaries. Most of the world’s newspapers reprinted the Jallianwala Bagh story and attributed the massacre to Michael O’Dwyer. Adham Singh was declared a freedom fighter and the Times newspaper described the incident as an expression of the outrage of the oppressed Indian people. In fascist countries, this event was used for propaganda against Great Britain.

A speaker at a public meeting in Kanpur termed the incident as ‘revenge for the insult and humiliation of the whole country’. Such sentiments were common across the country. The report on the political situation in Bihar said: ‘It is true that we could not bear the departure of Sir Michael because he had dishonored our country.’

During the trial, Udham Singh said:

I did it because I hated it. she deserves it. He was the real bully. He tried to crush the spirit of my nation, so I crushed him. For 21 years I was preparing to take revenge. I’m glad it’s finally done. I have no fear of death. I am giving my life for my country. I have seen people groaning with hunger in India under British rule. It was my duty to oppose it. What can be better than sacrificing one’s life for the motherland?

Adham Singh was hanged on 31 July 1940. In 1952, India’s Prime Minister Nehru declared Udham Singh a “great martyr” who died for independence.

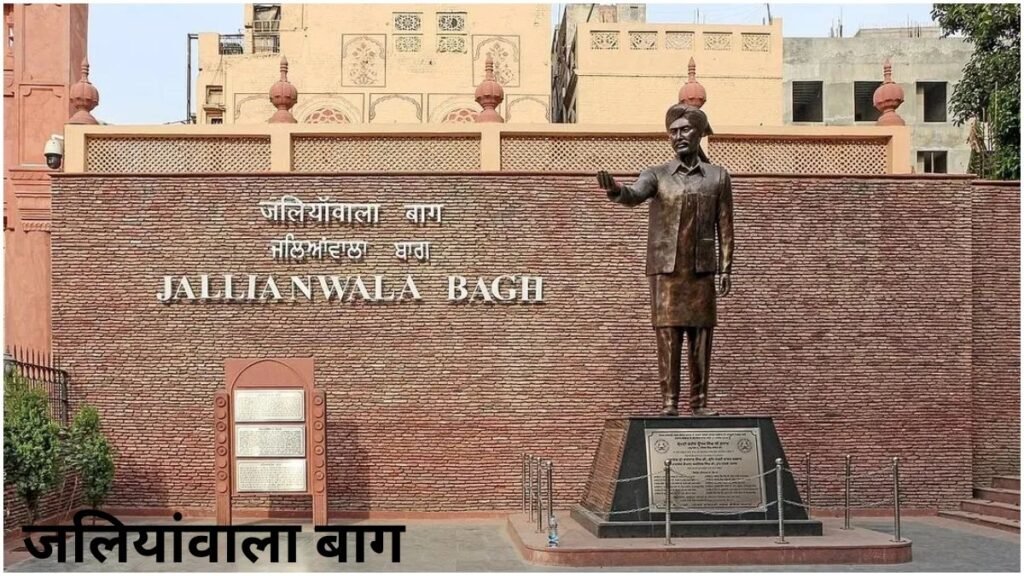

Memorial

In 1920, the Indian National Congress formed a trust to set up a memorial at the site of the incident. In 1923, the trust bought the site for the project. The monument was designed by American architect Benjamin Polk. It was inaugurated on 13 April 1961 by the President of India Rajendra Prasad in the presence of Jawaharlal Nehru and others. Later, a permanent light was also established at this place.

The marks of the bullets still remain on the walls and surrounding houses. A memorial has also been set up at the well in which people jumped to escape the bullets.

Formation of Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee

After the massacre, government officials at the Golden Temple debated whether to award ‘Saroop’ (for meritorious service to Sikhs in particular and humanity in general) to Colonel Dyer, and this led to an outcry among the Sikhs.

On October 12, 1920, in a meeting held at Amritsar Khalsa College, students and teachers demanded to take over the Gurdwaras from the Mahants. On November 15, 1920, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee was formed to take over the management of Sikh holy places and implement reforms.

British Prime Minister’s statement

On the occasion of the partition of India in 1947, Clement Richard Attlee, the successor of Winston Churchill, speaking in the House, said that today we are proud of the achievements of our comrades in India.

To express regret

Although Queen Elizabeth II did not comment on the massacre during her visits to India in 1961 and 1983, at a state dinner on October 13, 1997, she said:

In fact, there have been many difficult times in our past, including the painful example of Jallianwala Bagh. I will go there tomorrow. But history cannot be changed no matter how hard we try. It has its moments of sadness and joy. We should learn from the pain and store up the happiness for ourselves.

On October 14, 1997, Queen Elizabeth II visited Jallianwala Bagh and observed a half-minute silence to express her feelings. At that time, the queen wore saffron, a color of religious importance to Sikhism. On reaching the memorial, he took off his shoes and offered flowers.

Although the Indian people accepted the queen’s expression of remorse and grief, some critics say it was not an apology. However, the then Indian Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral defended Rani and said that Rani was not even born when the incident took place.

On July 8, 1920, Winston Churchill called for the impeachment of Colonel Dyer in the House of Representatives. Churchill persuaded the House to force Colonel Dyer into retirement, but Churchill wanted the colonel punished.

In February 2013, David Cameron was the first British Prime Minister to visit the site and called the Amritsar massacre “one of the most shameful events in British history”. However, Cameron has not officially apologized.

Jallianwala incident in writing and films

- 1977: Hindi language film named ‘Jallianwala Bagh’ was released. The film was written and produced by Balraj Taj. The film depicts the events of Udham Singh’s life. Part of the film was shot in the UK.

- 1981: Salman Rushdie’s novel ‘Midnight’s Children’ tells the story of the massacre from the point of view of a doctor who was present there and survived by sneezing in time.

- 1982: Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi depicts the event and Edward Fox plays General Dyer. The film depicts the events of the massacre and the subsequent investigation.

- 1984: The story of the massacre is narrated by the fictional widow of a British officer in episode 7 of Granada TV’s 1984 series The Jewel in the Crown.

- 2002: The Hindi film ‘The Legend of Bhagat Singh’ was directed by Rajmakar Santoshi. The film featured Bhagat Singh as a child witnessing the massacre that later helped him become a Hurriyat.

- 2006: The massacre was also shown in parts of the Hindi film ‘Rang De Basanti’.

- 2009: A part of Bali Rai’s novel ‘City of Ghosts’ is about this massacre.

- 2014: There is some mention of this massacre in the eighth episode of the fifth season of the British drama ‘Downtown Abbey’.