A sprawling burial site tucked away near a remote village in India has become the focal point of a fascinating archaeological discovery, shedding light on one of the world’s earliest urban civilizations. In this exploration, we delve into the cryptic clues that these graves may offer about the lives and deaths of early Indians.

The Mystery of the Mass Cemeteries of Early Indians

In 2019, a team of scientists embarked on an excavation mission to unearth the secrets concealed beneath a mound of sandy soil near a remote village in the scarcely populated Kutch region. Situated not far from Pakistan in India’s western state of Gujarat, their initial assumptions about the site were swiftly overturned. What they believed to be an ancient settlement soon revealed itself as a sprawling cemetery.

Rajesh SV, an archaeologist from the University of Kerala who spearheaded the excavation, recounts, “When we began digging, we thought it was an ancient settlement. Within a week, we realized it was a cemetery.”

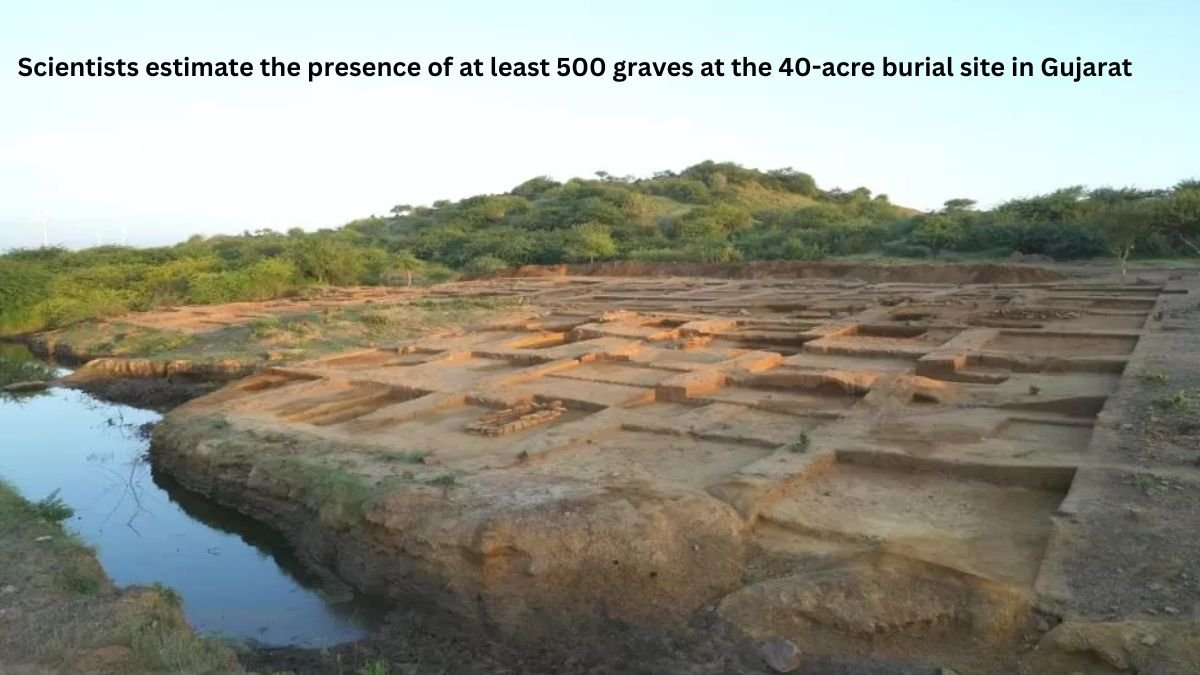

Three excavation seasons, involving over 150 Indian and international scientists, have transpired thus far at this 40-acre site. Their estimations suggest that the site houses a minimum of 500 graves from the Indus society, one of the earliest urban civilizations globally. Approximately 200 of these graves have been meticulously excavated.

Also referred to as the Harappan civilization, named after its inaugural city, this society comprised modest farmers and traders who dwelled within fortified, brick-built cities. Its zenith dates back approximately 5,300 years, in the north-western regions of present-day India and Pakistan. Over the course of a century since its initial discovery, researchers have uncovered around 2,000 sites scattered across India and Pakistan.

The researchers propose that the extensive burial ground near Khatiya village in Gujarat may potentially be the largest “pre-urban” cemetery associated with the Indus society uncovered thus far. It is believed to have been in use for approximately 500 years, spanning from 3200 BC to 2600 BC, making some of the oldest graves here around 5,200 years old.

Thus far, the excavations have yielded a solitary intact male human skeleton, along with partially preserved skeletal remains, including fragments of skulls, bones, and teeth. Additionally, an assortment of burial artifacts has been unearthed, featuring over 100 bangles and 27 beads crafted from shells. Among these discoveries are ceramic vessels, bowls, dishes, pots, small pitchers, beakers, clay pots, water cups, bottles, and jars. Notably, some treasures include beads made from the semi-precious stone, lapis lazuli.

The graves exhibit unique characteristics, such as sandstone-lined burial shafts pointing in various directions. These graves come in diverse shapes, including oval and rectangular. Some of the graves are smaller, signifying the resting place of children. Although the bodies seem to have been laid in a supine position, most of the bones have dissolved due to the acidic nature of the soil.

Brad Chase, a professor of anthropology at Albion College, Michigan, lauds this discovery as “hugely significant.” He notes that while several pre-urban cemeteries have been uncovered in Gujarat, this one stands out as the largest, potentially offering insights into a broader array of grave types and enriching our understanding of pre-urban society in the region.

Previous excavations in the Punjab region of present-day Pakistan have provided some insights into the burial customs of the Indus people. Unlike the ostentatious funerals of elites in Egypt and Mesopotamia, Indus funerals were understated. The deceased were not accompanied by jewels or weapons for the afterlife. Instead, most bodies were shrouded in textile and placed within rectangular wooden coffins. Pottery offerings were commonly placed within the grave pit before lowering the coffin.

Jonathan Mark Kenoyer of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a scholar of the Indus Valley civilization, notes that some individuals were buried with personal adornments like bangles, beads, and amulets. Specific items, such as copper mirrors and various vessels for serving and storing food, were also found. Notably, shell bangles were typically found on the left arms of adult females, while infants and children were not usually buried with pottery or ornaments.

The Mystery of Gujarat’s Vast Burial Ground Persists

The graves discovered in Gujarat’s sprawling burial ground continue to baffle scientists due to the absence of substantial wealth offerings. Furthermore, the health profiles of the individuals interred here indicate overall well-being, with some instances of arthritis and physical stress. While this monumental burial ground conceals its secrets, scientists remain committed to unraveling the mysteries it guards.

One of the most intriguing facets of these graves is the conspicuous absence of significant wealth, a departure from the customary practice of burying valuable items with the deceased in ancient civilizations. Instead, these resting places seem to convey a sense of simplicity, prompting questions about the societal structure and beliefs of the Indus people.

The discovery itself was serendipitous. In 2016, a village headman who also served as a driver led a group of University of Kerala archaeology students on a tour of the region. During this excursion, he guided them to the site, setting in motion the unfolding saga of a remarkable archaeological find.

The burial ground lay just 300 meters (985 feet) from Khatiya, a tiny village of 400 people, where inhabitants eked out a living by cultivating rainfed crops such as groundnut, cotton, and castor. Some of their farms bordered the graveyard. Previously, fragments of pottery and other artifacts had surfaced after rains, leading some to believe the area was haunted. However, the villagers had no inkling that they lived adjacent to such a significant burial site.

Narayan Bhai Jajani, the former headman of the village, reflects on the transformation, saying, “Now every year we have scientists from all over the world visiting our village and trying to find out more about the people who were buried here.”

The sheer volume of burials in one location raises intriguing questions about the purpose of this burial ground. Did it serve as a communal resting place for a cluster of nearby settlements, or does it hint at the existence of a larger settlement that remains hidden? Additionally, could it have functioned as a sacred cemetery for nomadic travelers, considering that the nearest source of lapis lazuli, found in these graves, likely originates from distant Afghanistan? Alternatively, could it have served as a “secondary” burial site, where bones from the deceased were interred separately?

“We still don’t know. We haven’t found a settlement in the neighborhood yet. We are still digging,” says Abhayan GS, an archaeologist at the University of Kerala. Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, a scholar of the Indus Valley civilization, expresses confidence that “there must be some settlements that relate to the cemetery, but they are probably lying beneath modern habitations or remain undiscovered.” Notably, the presence of well-constructed stone walls in the burials suggests that the people possessed knowledge of stone construction, and such stone structures and walled settlements have been identified within a 19-30km (11-18 miles) radius of the cemetery.

Further chemical studies and DNA testing of the human remains hold the promise of unveiling more about the earliest inhabitants of this region.

As mysteries about the Indus civilization endure, including the undeciphered script, scientists plan to excavate a site north of the cemetery near Khatiya in the coming winter. Their aim is to uncover a potential settlement. If successful, this discovery would solve one part of the puzzle, but if not, the relentless quest for answers through continued excavation will persist. Rajesh SV, the archaeologist who led the initial search, optimistically states, “Someday, hopefully, sooner than later, we will have some answers.”